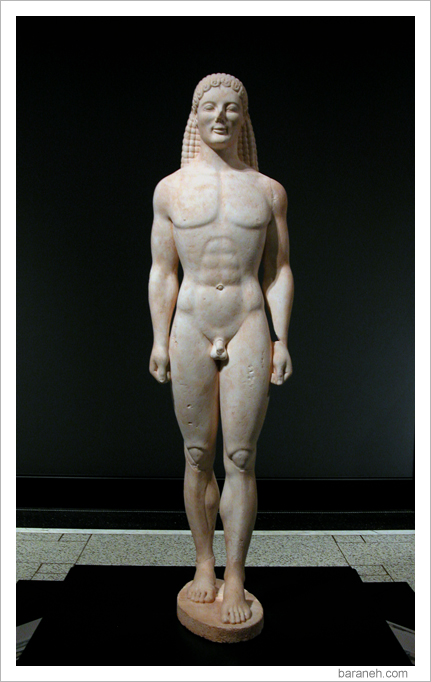

쿠로스상기원전 590– 580년경

그리스, 아티카

이 쿠로스(청년)는 아티카에서 조각된 인물조각상 중 가장 오래된 것 중 하나입니다. 왼발을 앞으로 내밀고 옆구리에 양팔을 붙인 경직된 자세는 이집트 미술에서 유래하였습니다. 그리스 조각가들은 기원전 6세기 내내 이 단순 명료한 자세를 사용하였습니다. 거의 추상에 가까운 기하학적 형태는 이러한 초기 조각상에서 주로 나타나며, 인체구조 세부도 이와 유사한 아름다운 기하학적 패턴으로 묘사되었습니다. 이 조각상은아테네의 어느 젊은 귀족의 묘 표석이었습니다.

The Term "kouros"

In ancient Greek the word "kouros" (plural, "kouroi") means male youth, and at least from the fifth century, specifically an unbearded male. Modern art historians have decided to use the term to refer to this specific type of a male nude standing with fists to its sides and left foot forward. Ancient Greeks would proably not have separated these figures from any of the other types of archaic sculptures of young men. Until the 1890s, when the term "kouros" was first applied to this type, scholars generally referred to these figures as Apollos as it was believed that all kouroi depicted Apollo. And as we shall see, this is definitely not the case.

Homer uses the word "kouros" in the Iliad to refer to young warriors. You might note that Lattimore translates the term variously. At the end of BK II at lines 510, 551 and 562 for example, he translates it as "son" or "sons," while in BK I he uses "young men" at 470. Among the texts available for searching in Perseus, the term occurs most frequently in Homer, and appears to be rather rare in later works. If you are interested, go to Perseus to find the passages where Homer uses the term. If you follow the Perseus link here click at the bottom of the page on the various forms of the word "kouros" to bring up the references and passages in Greek. For the English take the references provided and look them up in your Lattimore translation because Perseus uses a different English translation.

Introduction

The term "kouros"

Looking at a kouros

The Egyptian Connection

Beyond Looking: Functions and Meanings

From Archaic Texts to Archaic Contexts

Mimesis

Kouroi: An Aristocratic Ideal?

Archaic "Artists"

Bibliography

Images of Kouroi

Looking at a kouros

As the Stewart quote at the top of this page suggests, one of the key features of kouroi is their form. Analysing one kouros in detail allows us to identify aspects of this type of sculpture which in turn help us understand it within its cultural context.

The figure to the left shows an unclothed young man striding forward. Something you cannot tell from the image is that this kouros is slightly less than two meters tall, or just over life size, a pretty typical size for kouroi in general. The figure was almost certainly painted so that the figure was skin-toned in hue with details like eyes, lips and hair picked out in appropriate colors.

This figure is known as the Metropolitan kouros after the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, its present owner. The sculptor who carved this work is usually referred to as the Master of the Metropolitan Kouros or more simply the Met master. The anonymity of the figure's maker is not at all unusual for the Archaic period. Like most craftsmen in antiquity, we know nothing about the Met Master not even his name. Even if we had the name it would only be a name and offer us little, if any, further insight into the work or its production, except perhaps to suggest the region of Greece where the sculptor was from. In the Archaic era, his name was not thought worth preserving. We see here his only known work, and all that we know about him is that his medium was stone sculpture, specifically marble sculpture.

The anonymity of the makers of kouroi may trouble you. If it does, the problem is not surprising because our culture thinks that the names of sculptors and what they think about their work, is not only worth knowing, but perhaps even central to our understanding of their work. Not so in Ancient Greece. In the Archaic period, sculptors' names were usually not thought worth preserving. We'll come back to consider the role of the artist, or more properly put, the craftsmen in antiquity

Like all kouroi, the Met kouros is entirely freestanding. That is, the figure is carved on all sides, and although in our image the kouros is set back against a wall, if it were standing at the center of a room we would want to walk all around it to view each side. We are presented with four separate or independent faces that preserve the four sides of the original marble block from which the figure was carved. Moving around the figure is like turning four corners. Nothing bends or curves from one side to the other. This does not mean that the sculptor treats all 360 degrees of the statue equally. The statue's head, feet and hands all point rigidly straight forward emphasizing the frontal view. As a standing figure, the statue is taller than it is wide. Its vertical orientation is emphasized by a central axis running vertically between the legs, through the navel, the cleft of the chest and between the eyes. When viewed frontally the figure is disposed symmetrically about this central axis.

The statue stands on massive feet, firmly planted on a base. Neither leg rises vertically. The left leg strides forward and the right lags slightly behind the vertical of the torso so as to define an acute triangle. Though geometrically and therefore visually stable, the figure appears flat footed. In profile, the back protrudes above the chest and descends as a gently undulating curve outlining the volumes of the buttocks, the thighs, the calves and the heels. Seen straight on, the figure's curvilinear contours articulate the volumes of the different body parts. For example, from the chest, the contour tapers inward to the long narrow waist, only to bulge again at the thighs.

Moving from the exterior contour of the figure to the actual volumes of the main mass of the body, we see that the sculptor carefully renders selective anatomical details. For example, we find the pectoral muscles across his chest. But aside from the upper edges of the rib cage, there is nothing indicating the stomach muscles across the midriff. In contrast to the fluid and continuous lines of the outer contours, these selective anatomical details of muscles and bones within the body, especially the torso, form boundaries that separate the body into distinct parts. For example, the knees separate the upper from the lower legs; the pelvic lines, the legs from the torso; and the clavicle or collar bone the neck and head from the torso.

The craftsman who made this work also has a particular approach to the anatomical details he carved. Note, that the surface of the statue does not rise and fall as if muscles and bones were rippling somewhere beneath. On close inspection, we would see that the anatomy is indicated by clearly defined sharp ridges and shallow grooves so that the details appear to lie on the surface. In the overall visual effect, the details of the human body have been reduced to a surface pattern. Such patterning is typical of kouroi and archaic art in general. Pollitt (pp. 5-6), you may recall, makes this point in relation to earlier the bronze horse now in Berlin.

This desire to pattern detail in the Met kouros is best seen in the treatment of the figure's head. The mass of densely textured hair is divided into separate braids which are in turn divided into uniform globules. Seen straight on from the front, the rows of the design echo the arc defined by the eyes. From the side, the curves of the braids arching away from the forehead and down towards figure's back echo the curves of the top of the ear. Similarly the outer edge of the ear continues the curve of the jaw, while the ear itself, treated as a single flat surface, is a complex interplay of curves and counter curves repeating and echoing each other.

Returning to the full figure, we can see now how the sculptor uses pattern to organize the entire body. For example, the torso is dominated and structured by a series of Vee-shaped forms that are distributed in a strict hierarchy. The strongest is the great Vee of the groin ridge at the torso's lower limits. Only slightly less pronounced are the Vees of the collar bones at the upper extremity. Intermediary divisions are marked by inverted forms of these two shapes. An upside down Vee marks the upper limits of the rib cage. While the wing shape of the clavicles is turned upside down to form the double curve of the pectorals which delimit the lower edge of the chest. Note that these secondary divisions are less strongly indicated than the major ones. What is important here is not the strict imitation of the human form, but rather the use of the human form to create a sense of pattern.

The sculptor uses these divisions of the body to establish a set of rigid proportions based on simple mathematical relationships. Most obviously, the width of the figure is equal to its depth and approximately one quarter of its total height. The body is proportioned so that the distance from the base of the foot to the base of the knee cap is also one quarter of the figure's total height. This one to four proportion based on the total height is also found with the distance between the navel and the chin, and between the top of the head and the base of the neck at the clavicles. The latter relationship makes the head itself one sixth of the statue's height. Far larger in proportion than one observes on the actual human body, the height of the kouros's head corresponds exactly to the width of the figure at its hips.

We could go on much further with this sort of examination, but you should by now, see how it works. Close analysis of the statue reveals a certain approach to designing the figure. In examining this sculpture we have seen that its maker stresses a clear division of parts. He does this through stressing the surface of his figure by using a pattern based on selective anatomy. He's clearly not interested in every anatomical detail that exists on a male body, but only those that help organize his design. All the parts of the figure relate to the whole by a simple system of whole number proportions. When we compare this kouros with other sculptures of the period from the Greek world, we find that it shares with them many of the same formal characteristics we just outlined above. The style defined by these shared characteristics has been named Archaic.

To next section: The Egyptian Connection

Introduction

The term "kouros"

Looking at a kouros

The Egyptian Connection

Beyond Looking: Functions and Meanings

From Archaic Texts to Archaic Contexts

Mimesis

Kouroi: An Aristocratic Ideal?

Archaic "Artists"

Bibliography

Images of Kouroi

The “Getty Kouros” was removed from view at the museum after it was officially deemed to be a forgery.

The authenticity of the kouros (a freestanding Greek sculpture of a naked youth) has been debated since the Getty acquired the object in the mid-1980s for around $9 million. Despite the controversy, the work remained on view at the Los Angeles museum, next to a plaque reading “Greek, about 530 B.C. or modern forgery,” the New York Times reported. But it will no longer be up to viewers to weigh whether the object is authentic or not. Following a renovation of the Getty Villa, the sculpture was moved to storage where it will be on view by appointment only. “It’s fake, so it’s not helpful to show it along with authentic material,” said Getty director Timothy Potts. The removal is the final chapter in a decades-long saga that began when the Getty museum performed a battery of scientific tests on the piece to confirm its authenticity prior to purchase, only to buy the work and watch the faith in its authenticity slowly erode over time, the Times reported in 1991. A chemical process that occured on the exterior of the sculpture led scientists to believe the work must have been centuries old, but such a reaction was actually shown to be replicable in a lab. The additional investigation came after an indisputably fake torso similar to that of the Getty Kouros was discovered, causing some experts to reverse their position on the authenticity of the piece. Further investigation revealed that the curator who presented the kouros to the Getty for purchase forged the accompanying provenance documents.

Isaac Kaplan

4월 16, 2018 at 11:38am, via the New York Times

The Getty kouros is an over-life-sized statue in the form of a late archaic Greek kouros.[1] The dolomitic marble sculpture was bought by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California, in 1985 for ten million dollars and first exhibited there in October 1986.[2][3][4]

Despite initial favourable scientific analysis of the patina and aging of the marble, the question of its authenticity has persisted from the beginning. Subsequent demonstration of an artificial means of creating the de-dolomitization observed on the stone has prompted a number of art historians to revise their opinions of the work. If genuine, it is one of only twelve extant complete kouroi. If fake, it exhibits a high degree of technical and artistic sophistication by an as-yet unidentified forger. Its status remains undetermined: latterly the museum's label read "Greek, about 530 B.C., or modern forgery".[5] In 2018 the statue was removed from public display.[6]

Contents

Provenance[edit]

The kouros first appeared on the art market in 1983 when the Basel dealer Gianfranco Becchina offered the work to the Getty's curator of antiquities, Jiří Frel. Frel deposited the sculpture (then in seven pieces) at Pacific Palisades along with a number of documents purporting to attest to the statue's authenticity. These documents traced the provenance of the piece to a collection in Geneva of Dr. Jean Lauffenberger who, it was claimed, had bought it in 1930 from a Greek dealer. No find site or archaeological data was recorded. Amongst the papers was a suspect 1952 letter allegedly from Ernst Langlotz, then the preeminent scholar of Greek sculpture, remarking on the similarity of the kouros to the Anavyssos youth in Athens (NAMA 3851). Later inquiries by the Getty revealed that the postcode on the Langlotz letter did not exist until 1972, and that a bank account mentioned in a 1955 letter to an A.E. Bigenwald regarding repairs on the statue was not opened until 1963.[7] The documentary history of the sculpture was evidently an elaborate fake and therefore there are no reliable facts about its recent history before 1983. At the time of acquisition, the Getty Villa's board of trustees split over the authenticity of the work. Federico Zeri, founding member of board of trustees and appointed by Getty himself, left the board in 1984 after his argument that the Getty kouros was a forgery and should not be bought was rejected.[8][9]

Stylistic analysis[edit]

The Getty kouros is highly eclectic in style. Our understanding of the development of kouroi as delineated by Gisela Richter[10] suggests the date of the Getty youth diminishes from head to feet. Beginning with the hair we can observe that it is braided into a wig-like mass of 14 strands, each of which ends in a triangular point. The closest parallel here is to the Sounion kouros (NAMA 2720) of the late 7th century/early 6th century, which also displays 14 braids, as does the New York kouros (NY Met. 32.11.1). However, the Getty kouros's hair exhibits a rigidity, very unlike the Sounion Group. Descending to the hands, we may see that the last joints of the fingers turn in at right angles to the thighs, recalling the Tenea kouros (Munich 168) of the 2nd quarter of the 6th century. Further down, a late archaic naturalism becomes more pronounced in the rendering of the feet similar to kouros No. 12 from the Ptoon sanctuary (Thebes 3), as is the broad oval plinth which in turn is comparable to a base found on the Acropolis. Both Ptoon 12 and the Acropolis base are assigned to the Group of Anavyssos-Ptoon 12 and dated to the third quarter of the 6th century. Anachronizing elements are not unknown in authentic kouroi, but the disparity of up to a century is a strikingly unusual feature of the Getty sculpture.

Technical analysis[edit]

Side view of the kouros

Despite being of Thasian marble, the kouros cannot be securely ascribed to an individual workshop of northern Greece nor indeed to any ancient regional school of sculpture. Archaic kouroi conform to a canon of measurement and proportion (albeit with strong local accents) to which the Getty example also adheres; a comparison of like elements in other kouroi is both a test of authenticity and additional clue to the origin of the sculpture. There is little in the tool marks, carving methods and detailing to contradict an ancient origin of the piece. Although we have a small sample with which to compare (some 200 fragments and only twelve complete statues of the same type) there are atypical aspects of the Getty work that may be observed. The oval plinth is an unusual shape and larger than in other examples, suggesting the figure was free-standing rather than fixed with lead in a separate base. Also, the ears are not symmetrical: they are at different heights with the left oblong and the right rounder, implying the sculptor was using two distinct schema or none at all.[11] Furthermore, there are a number of flaws in the marble, most prominently on the forehead, which the sculptor has worked around by parting the hair curls at the centre; ancient examples survive of projects being abandoned by sculptors when such flaws in the stone were revealed.[12]

Frontal view

Perhaps the most striking evidence suggestive of the kouros's antiquity is a subtlety regarding the direction of motion of the figure. Even though the youth presents square to the viewer, all kouroi have understated indicators of a turn either to the left or the right depending on where they were originally placed in the temple sanctuary; i.e., they would seem to turn towards the naos. In the case of the Getty youth the left foot is parallel with the step axis of the right foot rather than turning outwards as would occur if the figure were moving directly forwards. Therefore, the statue is making motion toward his right, which Ilse Kleemann asserts is "one of the strongest pieces of evidence of its authenticity".[13] Other features that suggest a similarity with known originals include the helicoid curls of the hair, closest in form to the west Cyclidian Kea kouros (NAMA 3686), the Corinthian form of the hands and the sloping shoulders akin to the Tenea kouros and the broad plinth and feet comparable to the Attic or Cyclidian Ptoon 12. That the Getty kouros cannot be identified with any one local atelier does not disqualify it as a genuine, but if real it does require of us that we admit a lectio difficilior into the corpus of archaic sculpture.

Some indication of tool marks remain on the work. Though the surface is weathered (or artificially abraded) and it is not clear if emery was used, we can discern the heavy claw marks on the plinth and the use of a point in some of the finer detailing. For example, there are point marks in the outline of the curls, between the fingers and in the cleft of the buttocks, also traces of the point in the arches of the feet and at random over the plinth. Though the tools evident here (fine point, slope chisel, claw chisel) are not inappropriate for a late 6th century sculpture their application might be problematic. Stelios Triantis remarks, "no sculptor of kouroi would hollow out with a fine point, nor incise outlines with this tool".[14]

In 1990, Dr. Jeffrey Spier published the discovery of a kouros torso,[15] a certain forgery that exhibited notable technical similarities to the Getty kouros. After samples were taken that determined the fake torso was of the same dolomitic marble as the Getty piece the torso was purchased by the museum for study purposes. The fake's sloping shoulders and upper arms, volume of chest, rendering of the hands and genitals all suggest the same hand as the Getty's example, although the aging had been crudely done with an acid bath and the application of iron oxide. Further investigation has shown the torso and the kouros are not from the same block and the sculpting techniques are dramatically different (down to the use of power tools on the torso).[16] Their relationship if any is still to be determined.

Archaeometry[edit]

The Getty commissioned two scientific studies on which it based its decision to buy the statue. The first was by Norman Herz, a professor of geology at the University of Georgia, who measured the carbon and oxygen isotope ratios, and traced the stone to the island of Thasos. The marble was found to have a composition of 88% dolomite and 12% calcite, by x-ray diffraction. His isotopic analysis revealed that δ18O = -2.37 and δ13C = +2.88, which from database comparison admitted one of five possible sources: Denizli, Doliana, Marmara, Mylasa, or Thasos-Acropolis. Further, trace element analysis of the kouros eliminated Denizli. With the high dolomite content Thasos was determined to be the likeliest source with a 90% probability.[17] The second test was by Stanley Margolis, a geology professor at the University of California at Davis. He showed that the dolomite surface of the sculpture had undergone a process called de-dolomitization, in which the magnesium content had been leached out, leaving a crust of calcite, along with other minerals. Margolis determined that this process could occur only over the course of many centuries and under natural conditions, and therefore could not be duplicated by a forger.

In the early 1990s, the marine chemist Miriam Kastner produced an experimental result which cast doubt on Margolis's thesis by artificially inducing de-dolomitization in the laboratory, a result since confirmed by Margolis. Although this does admit the possibility that the kouros was synthetically aged by a forger, the procedure is a complicated and time-consuming one. The unlikeliness of a forger using such experimental methods in what is still an uncertain science has prompted the Getty's antiquities conservator to remark "when you consider a forger actually repeating the procedure you begin to leave the realm of practicality".[18]

See also[edit]

Media related to Getty Kouros at Wikimedia Commons

References[edit]

- ^ Getty Villa, Malibu, inv. no. 85.AA.40.

- ^ Thomas Hoving. False Impression, The Hunt for Big-Time Art Fakes, 1997, p. 298.

- ^ Sorensen, Lee. Frel, Jiří K. In The Dictionary of Art Historians. Accessed 28/8/2008.

- ^ MICHAEL KIMMELMAN. [1] In "ART; Absolutely Real? Absolutely Fake?". Accessed 26/1/2014

- ^ J. Paul Getty Museum. Statue of a kouros. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ^ L.A. Times Review: Something’s missing from the newly reinstalled antiquities collection at the Getty Villa retrieved 03/05/2020.

- ^ Marion True. The Getty Kouros: Background on the Problem, in The Getty Kouros Colloquium, 1993, p. 13.

- ^ Hanley, Anne (1998-10-07). "Obituary: Federico Zeri". The Independent. Retrieved 2014-01-09.

- ^ "Zeri, Federico". Dictionary of Art Historians. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ^ G.M.A. Richter. Kouroi: Archaic Greek Youths. A Study of the Development of the Kouros Type in Greek Sculpture.1970.

- ^ I. Trianti. Four Kouroi in One?, in The Getty Kouros Colloquium, 1993.

- ^ In the quarries of Naxos at Apollonas, Melanes and Flerio.

- ^ Ilse Kleemann, On the Authenticity of the Getty Kouros, in The Getty Kouros Colloquium, 1993, p. 46

- ^ Stelios Triantis. Technical and Artistic Deficiencies of the Getty Kouros in The Getty Kouros Colloquium, p. 52.

- ^ J. Spier. "Blinded by Science", The Burlington Magazine, September 1990, pp. 623–631.

- ^ Marion True, op. cit, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Norman Herz and Marc Waelkens. Classical Marble, 1988, p. 311.

- ^ Michael Kimmelman Absolutely Real? Absolutely Fake?, NYT, August 4th, 1991. Accessed 29/8/2008

Sources[edit]

- Robert Bianchi, Saga of The Getty Kouros, Archaeology (May/June 1994).

- Jerry Podany, Et Al., A Sixth Century B.C. Kouros in the J. Paul Getty Museum, J. Paul Getty Museum, 1992.

- Angeliki Kokkou (ed.), The Getty Kouros Colloquium: Athens, 25–27 May 1992, J. Paul Getty Museum, 1993.

- Norman Herz, Marc Waelkens, Classical Marble: Geochemistry, Technology, Trade, North Atlantic Treaty Organization Scientific Affairs Division, 1988.

- Jeffrey Spier, Blinded by Science: The Abuse of Science in the Detection of False Antiquities, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 132, No. 1050 (Sep., 1990), pp. 623–631.

- Marion True, A Kouros at the Getty Museum, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 129, No. 1006 (Jan., 1987), pp. 3–11.