From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Īśvarapraṇidhāna "commitment to the Īśvara ("Lord")"[1][2] is also one of five Niyama (ethical observances) in Hinduism and Yoga.[3][4]

Etymology and meaning[edit]

Īśvarapraṇidhāna is a Sanskrit compound word composed of two words īśvara (ईश्वर) and praṇidhāna (प्रणिधान). Īśvara (sometimes spelled Īshvara) literally means "owner of best, beautiful", "ruler of choices, blessings, boons", or "chief of suitor, lover". Later religious literature in Sanskrit broadens the reference of this term to refer to God, the Absolute Brahman, True Self, or Unchanging Reality.[5] Praṇidhāna is used to mean a range of senses including, "laying on, fixing, applying, attention (paid to), meditation, desire, prayer."[6] In a religious translation of Patanjali's Eight-Limbed Yoga, the word Īśvarapraṇidhāna means committing what one does to a Lord, who is elsewhere in the Yoga Sūtras defined as a special person (puruṣa) who is the first teacher (paramaguru) and is free of all hindrances and karma. In more secular terms, it means acceptance, teachability, relaxing expectations, adventurousness. [7]

Discussion[edit]

Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali[edit]

Īśvarapraṇidhāna is mentioned in the Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali as follows:[3]

Sanskrit: शौच संतोष तपः स्वाध्यायेश्वरप्रणिधानानि नियमाः ॥३२॥

– Yoga Sutras II.32

This transliterates as, "Śauca, Santoṣa, Tapas, Svādhyāya and Īśvarapraṇidhāna are the Niyamas". This is the second limb in Patañjali's eight limb Yoga philosophy is called niyamas which include virtuous habits, behaviors and ethical observances (the "dos").[8][9] The Yoga Sutras of Patañjali use the term Īśvara in 11 verses: I.23 through I.29, II.1, II.2, II.32 and II.45. Patañjali defines Īśvara (Sanskrit: ईश्वर) in verse 24 of Book 1, as "a special Self (पुरुषविशेष, puruṣa-viśeṣa)",[10]

Sanskrit: क्लेश कर्म विपाकाशयैःपरामृष्टः पुरुषविशेष ईश्वरः ॥२४॥

– Yoga Sutras I.24

This sutra of Yoga philosophy adds the characteristics of Īśvara as that special Self which is unaffected (अपरामृष्ट, aparamrsta) by one's obstacles/hardships (क्लेश, klesha), one's circumstances created by past or one's current actions (कर्म, karma), one's life fruits (विपाक, vipâka), and one's psychological dispositions/intentions (आशय, ashaya).[11][12]

Īśvarapraṇidhāna is listed as the fifth niyama by Patañjali. In other forms of yoga, it is the tenth niyama.[13] In Hinduism, the Niyamas are the "do list" and the Yamas are the "don't do" list, both part of an ethical theory for life.

Īśvara as a metaphysical concept[edit]

Hindu scholars have debated and commented on who or what is Īśvara. These commentaries range from defining Īśhvara from a "personal god" to "special self" to "anything that has spiritual significance to the individual".[14][15] Ian Whicher explains that while Patañjali's terse verses can be interpreted both as theistic or non-theistic, Patañjali's concept of Īśvara in Yoga philosophy functions as a "transformative catalyst or guide for aiding the yogin on the path to spiritual emancipation".[16] Desmarais states that Īśvara is a metaphysical concept in Yogasutras.[17] Īśvarapraṇidhāna is investing, occupying the mind with this metaphysical concept. Yogasutra does not mention deity anywhere, nor does it mention any devotional practices (Bhakti), nor does it give Īśvara characteristics typically associated with a deity. In yoga sutras it is a logical construct, states Desmarais.[17]

In verses I.27 and I.28, yogasutras associate Īśvara with the concept Pranava (प्रणव, ॐ) and recommends that it be repeated and contemplated in one of the limbs of eight step yoga.[18] This is seen as a means to begin the process of dissociating from external world, connecting with one's inner world, focusing and getting one-minded in Yoga.[18][19]

Whicher states that Patañjali's concept of Īśvara is neither a creator God nor the universal Absolute of Advaita Vedanta school of Hinduism. Whicher also notes that some theistic sub-schools of Vedanta philosophy of Hinduism, inspired by the Yoga school, prefer to explain the term Īśvara as the "Supreme Being that rules over the cosmos and the individuated beings".[20] However, in the Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali, and extensive literature of Yoga school of Hinduism, Īśvara is not a Supreme Ruler, Īśvara is not an ontological concept, rather it has been an abstract concept to meet the pedagogical needs for human beings accepting Yoga philosophy as a way of life.[20][21]

Īśvara as a deity[edit]

Īśvarapraṇidhāna has been interpreted to mean the contemplation of a deity in some sub-schools of Hinduism. Zimmer in his 1951 Indian philosophies book noted that the Bhakti sub-schools, and its texts such as the Bhagavad Gita, refer to Isvara as a Divine Lord, or the deity of specific Bhakti sub-school.[22] Modern sectarian movements have emphasized Ishvara as Supreme Lord; for example, Hare Krishna movement considers Krishna as the Lord,[23] Arya Samaj and Brahmoism movements – influenced by Christian and Islamic movements in India – conceptualize Ishvara as a monotheistic all powerful Lord.[24] In traditional theistic sub-schools of Hinduism, such as the Vishishtadvaita Vedanta of Ramanuja and Dvaita Vedanta of Madhva, Ishvara is identified as Lord Vishnu/Narayana, that is distinct from the Prakriti (material world) and Purusa (soul, spirit). In all these sub-schools, Īśvarapraṇidhāna is the contemplation of the respective deity.

Radhakrishnan and Moore state that these variations in Īśvara concept is consistent with Hinduism's notion of "personal God" where the "ideals or manifestation of individual's highest Self values that are esteemed".[25] Īśvarapraṇidhāna, or contemplation of Īśvara as a deity is useful, suggests Zaehner, because it helps the individual become more like Īśhvara. Riepe, and others,[26] state that the literature of Yoga school of Hinduism neither explicitly defines nor implicitly implies, any creator-god; rather, it leaves the individual with freedom and choice of conceptualizing Īśvara in any meaningful manner he or she wishes, either in the form of "deity of one's choice" or "formless Brahman (Absolute Reality, Universal Principle, true special Self)".[27][28][29] The need and purpose of Īśvara, whatever be the abstraction of it as "special kind of Self" or "personal deity", is not an end in itself, rather it is a means to "perfect the practice of concentration" in one's journey through the eight limbs of Yoga philosophy.[30][26]

Īśvara as pure consciousness[edit]

Larson suggests Īśvara in Īśvarapraṇidhāna can be understood through its chronological roots. Yoga school of Hinduism developed on the foundation of Samkhya school of Hinduism. In the non-theistic/atheistic Samkhya school, Purusa is a central metaphysical concept, and envisioned as "pure consciousness". Further, Purusa is described by Samkhya school to exist in a "plurality of pure consciousness" in its epistemological theory (rather than to meet the needs of its ontological theory).[31][32] In the Yoga Sutras, Patanjali defines Īśhvara as a "special Purusa" in verse I.24, with certain characteristics. Īśhvara, then may be understood as one among the plurality of "pure consciousness", with characteristics as defined by Patanjali in verse I.24.[31][33]

Īśvara as spiritual but not religious[edit]

Van Ness, and others,[34] suggests that the concepts of Īśvara, Īśvara-pranidhana and other limbs of Yoga may be pragmatically understood as "spiritual but not religious".[35][36]

See also[edit]

Notes and references[edit]

- Jump up^ N Tummers (2009), Teaching Yoga for Life, ISBN 978-0736070164, page 16-17

- Jump up^ Īśvara + praṇidhāna, Īśvara and praṇidhāna

- ^ Jump up to:a b Āgāśe, K. S. (1904). Pātañjalayogasūtrāṇi. Puṇe: Ānandāśrama. p. 102.

- Jump up^ Donald Moyer, Asana, Yoga Journal, Volume 84, January/February 1989, page 36

- Jump up^ Izvara ईश्वर, Monier Williams Sanskrit English Dictionary, Cologne Digital Sanskrit Lexicon, Germany

- Jump up^ Monier-Williams, Monier. "Sanskrit-English Dictionary". Monier Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- Jump up^ Patanjali. "Patanjalayogaśāstra". YS 1.24.

- Jump up^ N Tummers (2009), Teaching Yoga for Life, ISBN 978-0736070164, page 13-16

- Jump up^ Y Sawai (1987), The Nature of Faith in the Śaṅkaran Vedānta Tradition, Numen, Vol. 34, Fasc. 1 (Jun., 1987), pages 18-44

- Jump up^ Āgāśe, K. S. (1904). Pātañjalayogasūtrāṇi. Puṇe: Ānandāśrama. p. 25.

- Jump up^ aparAmRSTa, kleza, karma, vipaka and ashaya; Sanskrit English Dictionary, Koeln University, Germany

- Jump up^ Lloyd Pflueger (2008), Person Purity and Power in Yogasutra, in Theory and Practice of Yoga (Editor: Knut Jacobsen), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120832329, pages 31-45

- Jump up^ The Practice of Surrender Yoga Journal (August 28 2007)

- Jump up^ Lloyd Pflueger (2008), Person Purity and Power in Yogasutra, in Theory and Practice of Yoga (Editor: Knut Jacobsen), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120832329, pages 38-39

- Jump up^ Hariharānanda Āraṇya (2007), Parabhaktisutra, Aporisms on Sublime Devotion, (Translator: A Chatterjee), in Divine Hymns with Supreme Devotional Aphorisms, Kapil Math Press, Kolkata, pages 55-93; Hariharānanda Āraṇya (2007), Eternally Liberated Isvara and Purusa Principle, in Divine Hymns with Supreme Devotional Aphorisms, Kapil Math Press, Kolkata, pages 126-129

- Jump up^ Ian Whicher (1999), The Integrity of the Yoga Darsana: A Reconsideration of Classical Yoga, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791438152, page 86

- ^ Jump up to:a b Michele Marie Desmarais (2008), Changing Minds : Mind, Consciousness And Identity In Patañjali's Yoga-Sutra, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120833364, page 131

- ^ Jump up to:a b Michele Marie Desmarais (2008), Changing Minds : Mind, Consciousness And Identity In Patañjali's Yoga-Sutra, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120833364, page 132-136

- Jump up^ See Yogasutra I.28 and I.29; Āgāśe, K. S. (1904). Pātañjalayogasūtrāṇi. Puṇe: Ānandāśrama. p. 33.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Ian Whicher, The Integrity of the Yoga Darsana, State University of New York press, ISBN 978-0791438152, pages 82-86

- Jump up^ Knut Jacobsen (2008), Theory and Practice of Yoga : 'Essays in Honour of Gerald James Larson, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120832329, page 77

- Jump up^ Zimmer (1951), Philosophies of India, Reprinted by Routledge in 2008, ISBN 978-0415462327, pages 242-243, 309-311

- Jump up^ Karel Werner (1997), A Popular Dictionary of Hinduism, Routledge, ISBN 978-0700710492, page 54

- Jump up^ Rk Pruthi (2004), Arya Samaj and Indian Civilization, ISBN 978-8171417803, pages 5-6, 48-49

- Jump up^ Radhakrishnan and Moore (1967, Reprinted 1989), A Source Book in Indian Philosophy, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691019581, pages 37-39, 401-403, 498-503

- ^ Jump up to:a b Mircea Eliade (2009), Yoga: Immortality and Freedom, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691142036, pages 73-76

- Jump up^ Dale Riepe (1961, Reprinted 1996), Naturalistic Tradition in Indian Thought, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120812932, pages 177-184, 208-215

- Jump up^ RC Zaehner (1975), Our savage god: The perverse use of eastern thought, ISBN 978-0836206111, pages 69-72

- Jump up^ RC Zaehner (1966), Hinduism, Oxford University Press, 1980 edition: pages 126-129, Reprinted in 1983 as ISBN 978-0198880127

- Jump up^ Woods (1914, Reprinted in 2003), Yoga system of Patanjali, Harvard University Press, pages 48-59, 190

- ^ Jump up to:a b Ian Whicher, The Integrity of the Yoga Darsana, State University of New York press, ISBN 978-0791438152, pages 80-81

- Jump up^ N Iyer (2008), Theory and Practice of Yoga : 'Essays in Honour of Gerald James Larson (Editor: Knut Jacobsen), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120832329, pages 103-104

- Jump up^ Lloyd Pflueger (2008), Person Purity and Power in Yogasutra, in Theory and Practice of Yoga (Editor: Knut Jacobsen), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120832329, pages 32-39

- Jump up^ B Pradhan (2014), Yoga: Original Concepts and History. In Yoga and Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy, Springer Switzerland, ISBN 978-3-319-09104-4, pages 3-36

- Jump up^ Peter H. Van Ness (1999), Yoga as Spiritual but not Religious: A pragmatic perspective, American Journal of Theology & Philosophy, Vol. 20, No. 1 (January 1999), pages 15-30

- Jump up^ Fritz Allhoff (2011), Yoga - Philosophy for Everyone: Bending Mind and Body, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0470658802, Foreword by J

Photo by Ali Kaukus

This is the final part of a 10-part series exploring each of the Yamas and Niyamas to discover how we can incorporate them both on and off the mat for a deeper, richer life of yoga.

Several years ago I met a joyful Sufi woman who had been practicing a heart meditation morning, noon, and night for 40 years. Familiar with this powerful practice, I assumed she must have had some very beautiful experiences. So I asked her about it… But she hadn’t. While most people she knew had felt their hearts open, had visions, or had heard the voice of love, she supposed that—for her—the Divine had a different plan. But it mattered not one bit: She needed no proof. She was utterly devoted to love.

I was so moved and humbled by her devotion. To practice every morning and then throughout the day to meditate on—and for—the Divine for 40 years without any sign of being heard, or of being on the right path, and yet to remain steadfast in the practice… Faith that strong, that dedicated—I could not have imagined having.

“Surrender is the simple but profound wisdom of yielding to rather than opposing the flow of life.” – Eckhart Tolle

As devoted of yogis as we may be, we often carry with us an expectation of something in return for our dedication. We want results. We want peace and joy and love. We want to be better human beings. We want to be healed. We want the boons. How many of us can say we would keep returning to the cushion or mat if we hadn’t felt our bodies opening and our hearts responding?

Yet it is this unshakable faith and devotion that ishvara pranidhana, the final of our five Niyamas, wants us to cultivate. It can be translated as “devoting oneself entirely to the Divine,” and Patanjali mentions it more than any other Yama or Niyama. The gentle voice in the Yoga Sutras that began with ahimsa, saying—Let go of who you think you are, and become who you truly are—has now become a roar.

Why? Because we if want to experience our divine nature, we have to surrender our ego nature. We have to surrender from the “I” and return to love. Without ishvara pranidhana, there is no samadhi.

So what is this “I” we are giving up? It can seem scary, and lead us declare war on our ego… But there is no need for a battle. The ego is nothing more than a collection of false beliefs we have about who we are. So when we surrender from our ego, we aren’t giving up our personalities, our expressions in the world. We still love hip-hop music and lattes, and we still have our quirky sense of humor. Rather we are surrendering from the beliefs that we aren’t worthy, that we aren’t lovable, that we aren’t enough…

When we surrender, we instead bring the energy of yes to the present moment.

And through this act of surrender, we give up all the ways in which those false beliefs are expressing themselves in the world through our thoughts, emotions, and actions. We surrender the “you’re right/you’re wrong, I’m wrong/I’m right” behaviors that have driven our experience of life, and instead we see that everything is one, and therefore everything is perfect. How can it not be? Ishvara includes within it the understanding that the “Divine” is within everyone. And if the Divine is perfect and we are all divine, then how can anything be wrong?

Intellectually we can grasp this, but it is more challenging to live in surrender. The good news is that just by coming to yoga we have already started shedding our skins. And if we continue on this path, devoting ourselves to love rather than the “I”, then samadhi is inevitable.

So how do we practice ishvara pranidhana? We start saying “yes.” All the worrying, the striving, the thoughts of how we must do this, and must achieve that, the judging, and the complaining—that’s our mind saying no to what is. When we surrender, we instead bring the energy of yes to the present moment. That person who jumps ahead of us in line and makes us mad? In the words of spiritual teacher Brent Haskell, we say: “Yes, thank you—for you reminded me that I still think we are separate.” The presidential candidate we are vehemently against? We say: “Yes, another fine example of how I’m devoted to what I think matters, instead of allowing what is.”

As Eckhart Tolle says, surrender is the simple but profound wisdom of yielding to rather than opposing the flow of life.”

It is not weakness to yield. We will still vote. Rather we let our heart determine our choices instead of our minds. Indeed, when we start to practice ishvara pranidhana we ask in every moment, as advaita zen master Mooji teaches: “Divine, replace me with you.”

When we surrender we see through the eyes of love. We start to accept life in its crazy, beautiful entirety, and in doing so we free ourselves up to do what makes our heart sing. We begin to let the divine spark inside us express itself. Life becomes an adventure.

But we have to trust the outcome. When we are fully surrendering, we have no expectations. We are not looking for peace. We are peace. We are not looking to be made perfect. We are perfect. We practice yoga for our love of yoga, not because we want to be better people or think yoga is necessary. We live in the present, and we become like my Sufi friend—wholly open to what is, and devoted to love for love’s sake. This, says Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita, is the purest path to samadhi of all.

3 Ways to Put Ishvara Pranidhana Into Practice

1. Start Saying “Yes”

Every time you are triggered, see it as a sign to where your devotion lies. If you’re upset because your rent is hiked, that’s great! That means you’re not trusting what is, and your devotion is to money right now. If you’re offended because a colleague tells you you look terrible today, great! That means your devotion is to your body. In every moment we have a choice to say “yes” to the perfection in everything.

2. Take a Small Leap of Faith

“To fly as fast as thought, to anywhere that is, you must begin by knowing that you have already arrived,” says Richard Bach in Jonathan Livingstone Seagull. That is faith—the inner knowing. Sometimes we can take the large leap, but other times we need small steps. So start small: What does the Divine spark in you want to do today, in this moment? Take the train? Go by bus? Go left or go right? Begin to trust whatever happens along the way.

3. on the Mat

To embody ishvara pranidhana on our mat we must come to our practice with a heart of devotion. So we start with an offering. Perhaps we light incense or a candle. We focus on whatever form the Divine takes for us, and intend ourselves to surrender our will, to let ourselves be moved. We hand ourselves over.

With this energy we can approach every asana as a chance to explore where our resistance lies. Where are we clenching in Kapotasana? Is it resistance that blocks our headstand or Chakrasana? And through our practice we begin to understand that we are safe to surrender. When we move into a backbend being guided by the Divine, rather than from a sense of “I must…” we will find we are guided just to the point we need—no more.

And what better asana for allowing what is, than Savasana? Too often in class we rush through with a five-minute Savasana, so why not set aside time for a home practice that includes a 15-minute Savasana?

Finally, in meditation, we do as Zen Buddhist teacher Joan Halifax Roshi suggests: “We cross our legs and hope to die.” We hand over the ego and sit with unshakable faith in our anjali mudra, our mudra of devotion, and we surrender to love.

See all of the Yamas and Niyamas in this 10-part series here.

—

Helen Avery is a Section Editor at Wanderlust Media, working on the Vitality and Wisdom channels on Wanderlust.com. She is a journalist, writer, yoga teacher, Awakening Together minister, and full-time dog walker of Millie.

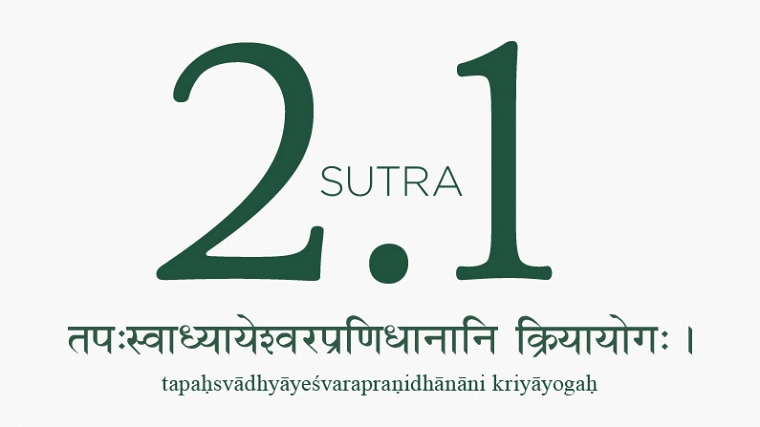

Translation

The schematic practice of yoga consists of three components: tapas (austerity), svadhyaya (self-study), and Ishvara pranidhana (unshakeable faith in the guiding and protecting power of God).

tapaḥsvādhyāyeśvarapraṇidhānāni = tapaḥ + svādhyāya + īśvarapraṇidhāna

tapaḥ derivative of tapas and tapa; as a verb, it means to heat; to glow; to shine; to purify; to fire; to change; to transform. In philosophical and spiritual literature, tapas refers to the practices and disciplines leading to acquiring radiance of body and clarity of mind; generally tapas refers to austerity, penance, and undertaking the practices that require putting the body and mind through hardship and thereby expanding one’s endurance.

We'll never share your info. Spam just isn't yogic.

svādhyāya = sva + adhyāya

- sva self; one’s own; pertaining to inner reality; belongingness

- adhyāya a chapter; a phase; a portion; a lesson; study

Together, svādhyāya means study of the self; study by oneself; understanding each and every chapter of life separately, as well as in relation to each other; a thorough study of oneself; thorough study of the scriptures.

īśvarapraṇidhāna = īśvara + praṇidhāna

- īśvara guiding and protecting force; the omniscient, primordial being; the teacher of all previous teachers; the soul free from all afflictions, karmas, and fruits of karmas

- praṇidhāna complete surrender; complete recognition; embracing tightly; keeping at the center of life

Together, īśvarapraṇidhāna refers to having complete faith in the guiding and protecting power of the Absolute Reality.

kriyāyogaḥ = kriyā + yoga

- kriyā action; effort; to initiate; to move with purpose and goal

- yoga the process of acquiring a calm and tranquil mind; the absolutely still state of mind

Together, kriyāyoga means an action plan for acquiring a calm and tranquil mind; an action plan for reaching an absolutely still state of mind. In other words, kriyāyoga means to put the theory of yoga into practice; the schematic practice of yoga.

3 Steps to Self-Transformation

The spiritual energy contained in a sacred mantra infuses self-study with purpose and meaning.

This is the first sutra of chapter 2, and as such, it is a continuation of the last sutra of chapter 1. The first chapter is known as Samadhi Pada, the chapter that expounds on samadhi. According to Patanjali, samadhi is the heart of yoga. Samadhi grants ultimate freedom—the freedom from all known and unknown causes of sorrow. Samadhi is the foundation of lasting joy, for it is free from all fears and doubts. In samadhi, the mind stands still and regains its ability to see reality as it is. The prerequisite for attaining samadhi, however, is to make ourselves completely free from the charms and temptations of the world and keep our focus on only one single reality—the inner self. This prerequisite implies that those who are not established in the virtue of dispassion (vairagya) are not fit to practice yoga as described in chapter 1. The commentator Vyasa clearly states that a disturbed, distracted, and stupefied mind is not fit for reaching samadhi. It is reachable only by aspirants who have cultivated a one-pointed and completely still mind.

The charms and temptations of the world agitate our minds, and an agitated mind is bound to be disturbed and distracted. When it meets failure in worldly endeavors, the mind gets frustrated and tired. Such a mind resorts to sloth and inertia and becomes stupefied.

Because living with a disturbed, distracted, and stupefied mind has become the norm for most of us, reaching a state of samadhi as described in the first chapter of the Yoga Sutra is beyond the scope of most people. Should we simply forget about practicing yoga because we do not have a disciplined, focused, purified, and perfectly still mind? No.The practice described in chapter 2 is specifically for those whose minds swing from disturbed to distracted to stupefied to one-pointed to perfectly still and back again.

We are all endowed with limitless capacities. Our dormant potentials are immense. Even the most unhealthy person, with the right planning and sustained effort, can become healthy in body and clear in mind. According to Patanjali, putting together a plan to discover one’s core strength and executing that plan systematically is called kriya yoga, the schematic practice of yoga. With this kind of yoga, you can start practicing from wherever you are. This schematic practice of yoga guides you to assess your current physical capacity, intellectual grasp, and emotional maturity, and, based on your findings, determine the scope and intensity of your practice. Thereafter, you walk one step at a time. This way, regardless of whether your mind is focused or relatively dissipated, whether it is sharp or relatively dense, you can start practicing yoga compatible with your current level of development. Knowing how to assess your ability and design a plan is the crux of this schematic practice.

Kriya yoga consists of three components: tapas, svadhyaya, and Ishvara pranidhana. Tapas helps us assess our physical capacity; svadhyaya, our mental ability and intellectual grasp. Ishvara pranidhana allows us to see the depth of our emotional maturity. Together these three help us see our strengths and weaknesses, and, with proper guidance, help us design a course of practice that is perfect for our overall growth and development. Let us examine these three components more closely.

Tapas is loosely translated as “austerity.” In an Indian context, austerity is normally associated with strict self-denial—fasting, owning no material objects, living in a cave or hut with only the bare necessities, and, in extreme cases, standing on one leg for years at a time, lying on a bed of nails, or not using one’s own hands to feed oneself. In Western culture, austerity is associated with monasticism—living in a monastery, doing penance, fasting, and practicing celibacy and non-possessiveness. In both East and West, austerity is associated with hardship. This notion of austerity runs counter to the fundamental goal and objective of tapas in yoga. Radiance and clarity are the core of tapas. A practice or discipline is tapas only when it can help us cultivate a radiant body and a clear mind. Tapas is not torture or hardship, but rather the ability to awaken the dormant energy within us. one who undertakes such a practice is called tapasvi.

At a practical level, tapas entails gathering the fire within—overcoming sloth and inertia, becoming active, not being dependent on others for your salvation, taking charge of your own destiny, and putting your intellectual knowledge into practice. Just as when putting a wheel into motion, you have to face the resistance caused by inertia; in the beginning stages of your practice, a great deal of energy goes into overcoming resistance. This causes discomfort. Enduring this discomfort is tapas. When you commit yourself to this discomfort without a true understanding of the higher goal and purpose of the practice, your mind perceives it as torture. Sooner or later, it becomes unbearable—and eventually you drop it. If you force yourself to continue, you will disturb the ecology of your body and mind. People who are not familiar with your inner world may perceive you as a mystic, but in reality you are merely in the grip of spiritual insanity. However, if you know why you are undertaking a practice, what its goal and objective is, how it can help you remove the inertia of body and confusion of mind, how it can infuse your heart with the light of higher reality, and, therefore, why enduring any hardship your practice may bring is a great opportunity, tapas can become a source of lasting joy.

How do you practice tapas? The first level of practice involves restoring your body to health. For those with an unwholesome lifestyle, adopting a healthy diet, proper exercise, and bringing regularity to their sleeping pattern is a big tapas. Deeply rooted habits do not like change. Summon your willpower, stick to your decision, and adopt a healthy lifestyle. That is the beginning point—spiritually enlightened austerity. This level of tapas brings the ecology of the body to a state of balance.

The practice of pranayama takes tapas to the next level. The classical texts consider pranayama to be the highest form of tapas. The Yoga Sutra clearly states that the practice of pranayama destroys the veil that hides the light. In other words, the fire of breath burns not only physical but also mental impurities. The practice of pranayama helps purify and strengthen the nervous system, awaken the dormant forces of consciousness at different chakras, and ultimately roast the seeds of karmas deposited deep in the mindfield. The practice of pranayama should be undertaken only after we are fully established in the practice of hatha yoga.

Other forms of tapas include mantra japa, selfless service, pilgrimage, and practicing truth in thought, speech, and action. Each of these helps us expand our physical capacity, enabling us one day to experience how limitless powers are deposited in this body—a subject fully described in chapter 3.

Svadhyaya is loosely translated as“self-study.” This conjures up the notion of studying without a teacher and is a totally erroneous understanding of this term. According to the Yoga Sutra and the commentator Vyasa, svadhyaya means to study oneself by the means of practicing sacred mantras and reflecting on moksha shastra, the scriptures devoted exclusively to the dynamics of ultimate freedom.

In the simplest language, self-study means to reflect on oneself—to reflect on who we are, what our true nature is, where we come from, our purpose in being here, how we relate to others, what our duties are in relation to others, what we did in the recent past and the consequences of that, what we are doing now and what the future consequences may be, how fulfilling life and its gifts are, and whether or not we will be able to leave this world with grace and dignity. This self-reflection finds a purpose and flows in the right direction with a definite goal when it is accompanied by japa of a sacred mantra. Without mantra japa, self-reflection can degenerate into an intellectual exercise. It is the spiritual energy contained in a sacred mantra that infuses self-study with purpose and meaning. It is important that the mantra chosen for this japa is sacred. The selection of mantra is crucial as not all mantras have spiritually illuminating energy.

Self-study is also to be accompanied by the study of the right kind of scriptures— those which have ultimate freedom of the soul as their focal point. Such scriptures are called moksha shastra and include the Bhagavad Gita, the Upanishads, the Yoga Vasishtha, and the Yoga Sutra itself. These scriptures set the guidelines and ensure that the direction of our self-reflection is correct. This kind of self-study helps us expand our mental ability and refine our intellectual grasp, which in turn empowers us with the conviction that the path we are walking on is straight and legitimate.

Ishvara pranidhana is loosely translated as “surrender to God.” This translation gives an impression of giving up and conveys a sense of inaction, passivity, and passing the responsibility for ourselves onto God. Such a notion of surrendering to God is misleading and completely wrong. The first step in practicing Ishvara pranidhana requires making an effort to comprehend the true meaning of Ishvara. Ishvara means unrestricted, unfettered, divine power. It is not only almighty but also all-knowing. It is auspicious, beginningless, and endless. It is all-pervading, the eye of the soul.

Unshakeable faith in the guiding and protecting power of God is the essence of Ishvara pranidhana. Infusing our actions with this faith is the second step. Surrendering the fruits of our actions and not being affected by the results of our actions is the final step.

Ishvara pranidhana is the final test of whether or not we are living in the presence of God. It helps us assess how mature we are in our beliefs, how resolute we are in our decisions, and how strong we are in removing ourselves in favor of God. There cannot be a more active way of performing one’s duty than Ishvara pranidhana: work hard with a surrendered attitude in the full realization that we are simply an instrument in the hands of the one who is almighty, omniscient, and the Lord of all that exists.

The schematic plan of yoga comprised of these three elements—tapas, svadhyaya, and Ishvara pranidhana—helps us detoxify the body, nurture the senses, and purify the mind. These three together help us cultivate a higher degree of endurance and fortitude. Thereafter, obstacles such as disease, procrastination, laziness, and doubt begin to lose their grip on us. The practice of yoga that leads to the stillness of mind then becomes natural and spontaneous.