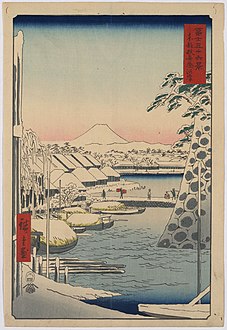

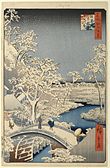

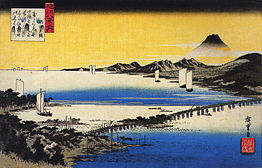

Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi bridge and Atake (1857) by Hiroshige

Japonaiserie (English: Japanesery) was the term the Dutch post-impressionist painter Vincent van Gogh used to express the influence of Japanese art.[1]

Before 1854 trade with Japan was confined to a Dutch monopoly and Japanese goods imported into Europe were for the most part confined to porcelain and lacquer ware. The Convention of Kanagawa put an end to the 200-year-old Japanese foreign policy of Seclusion and opened up trade between Japan and the West.

Artists including Manet, Degas and Monet, followed by Van Gogh, began to collect the cheap colour wood-block prints called ukiyo-e prints. For a while Vincent and his brother Theo dealt in these prints, and they eventually amassed hundreds of them, now housed in the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.[2]

In a letter to Theo dated about 5 June 1888 Vincent remarks

- About staying in the south, even if it’s more expensive—Look, we love Japanese painting, we’ve experienced its influence—all the Impressionists have that in common—[so why not go to Japan], in other words, to what is the equivalent of Japan, the south? So I believe that the future of the new art still lies in the south after all.[3]

A month later he wrote,

- All my work is based to some extent on Japanese art...[4]

Contents

[hide]Influence of Japanese art on Van Gogh[edit]

Van Gogh's interest in Japanese ukiyo-e prints dates from his time in Antwerp when he was also interesting himself in Delacroix's theory of colour and where he used them to decorate his studio.

- one of De Goncourt's sayings was 'Japonaiserie for ever'. Well, these docks [at Antwerp] are one huge Japonaiserie, fantastic, singular, strange ... I mean, the figures there are always in motion, one sees them in the most peculiar settings, everything fantastic, and interesting contrasts keep appearing of their own accord."[5]

During his subsequent stay in Paris, where Japonisme had become a fashion influencing the work of the Impressionists, he began to collect ukiyo-e prints and eventually to deal in them with his brother Theo. At that time he made three copies of ukiyo-e prints, The Courtesan and the two studies after Hiroshige.

Van Gogh developed an idealised conception of the Japanese artist which led him to the Yellow House at Arles and his attempt to form a utopian art colony there with Paul Gauguin.

His enthusiasm for Japanese art was later taken up by the Impressionists. In a letter of July 1888 he refers to the Impressionists as the "French Japanese".[6] He still strongly admired the techniques of Japanese artists, however, writing to Theo in September 1888:

- "I envy the Japanese the extreme clarity that everything in their work has. It's never dull, and never appears to be done too hastily. Their work is as simple as breathing, and they do a figure with a few confident strokes with the same ease as if it was as simple as buttoning your waistcoat."[7]

Van Gogh's dealing in ukiyo-e prints brought him into contact with Siegfried Bing, who was prominent in the introduction of Japanese art to the West and later in the development of Art Nouveau.[8]

Characteristic features of ukiyo-e woodprints include their ordinary subject matter, the distinctive cropping of their compositions, bold and assertive outlines, absent or unusual perspective, flat regions of uniform colour, uniform lighting, absence of chiaroscuro, and their emphasis on decorative patterns. one or more of these features can be found in numbers of Vincent's paintings from his Antwerp period onwards.

The Courtesan (after Eisen)[edit]

The May 1886 edition of Paris Illustré was devoted to Japan with text by Tadamasa Hayashi who may have inspired van Gogh's utopian notion of the Japanese artist:

- "Just think of that; isn’t it almost a new religion that these Japanese teach us, who are so simple and live in nature as if they themselves were flowers?"

- "And we wouldn’t be able to study Japanese art, it seems to me, without becoming much happier and more cheerful, and it makes us return to nature, despite our education and our work in a world of convention." [9]

The cover carried a reverse image of a colour woodblock by Keisai Eisen depicting a Japanese courtesan or Oiran. Vincent traced this and enlarged it to produce his painting.

Copies of Hiroshige prints[edit]

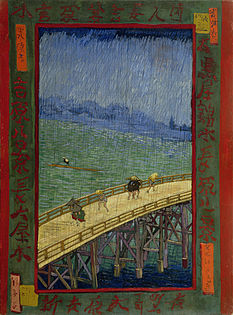

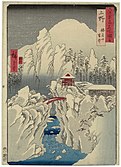

Van Gogh made copies of two Hiroshige prints. He altered their colours and added borders filled with calligraphic characters he borrowed from other prints.[10]

Example ukiyo-e colour woodblock prints[edit]

- Eisen: The Feast of Seven Herbs.[11]

- Eisen and others: 22 Japanese woodcuts, Connecticut College, Connecticut

- Eisen: Opening Night in the Theater District for Two Theaters of Edo (Edo ryôza Shibai-machi kaomise no zu).[12]

- Hiroshige: Sudden Shower over Atake (1857), Brooklyn Museum, New York

- Hiroshige: Plum Estate, Kameido (1857), Brooklyn Museum, New York

- Hiroshige: Maple Trees at Mama, Tekona Shrine (1857), Brooklyn Museum, New York

- Hiroshige: Ushimachi, Takanawa (1857), Brooklyn Museum, New York

- Hiroshige: Fireworks at Ryōgoku (1857), Brooklyn Museum, New York

- Hiroshige: Yui, Satta Peak.[13]

- Hiroshige: (various).[14]

- Hokusai: Abe No Nakamaro, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

- Hokusai (attrib.): The Shishi-Mai Dance, Royal Academy of Arts, London

- Sharaku: The Actors Nakamura Wadaemon and Nakamura Konoz.[15]

- Utamaro: Girl at her Toilet with two female attendants and male admirer, Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, Birmingham

- Utamaro: Women sewing.[16]

- Utamaro: Picture Book of Crawling Creatures (1788)s, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Illustrative Van Gogh oil paintings on canvas[edit]

In the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam[edit]

- Houses seen from the Back (1885, Antwerp).[17]

- The Courtesan (1887).[18]

- The Bridge in the Rain (after Hiroshige), (1887).[19]

- Flowering Plum Orchard (after Hiroshige), (1887).[20]

- Sprig of Flowering Almond in a Glass (1888).[21]

- The Bedroom (1888).[22]

- Fishing Boats on the Beach at Les Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer (1888).[23]

- The Rock of Montmajour with Pine Trees (1888), pen and brush.[24]

- The Langlois Bridge (1888).[25]

- The Harvest (1888).[26]

- The Sower (1888).[27]

- Almond Blossom (1890).[28]

Outside Holland[edit]

- Vincent's Chair with Pipe (1888), National Gallery, London

- Sunflowers (1888), National Gallery, London

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Search result". Vincent van Gogh. The Letters. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum.

- ^ "Japanese prints: Catalogue of the Van Gogh Museum's collection". Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum.

- ^ "Letter 620". Vincent van Gogh. The Letters. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum.

- ^ "Letter 640". Vincent van Gogh. The Letters. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum.

- ^ "Letter 545". Vincent van Gogh. The Letters. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum.

- ^ "Letter 642". Vincent van Gogh. The Letters. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum.

- ^ "Letter 686". Vincent van Gogh. The Letters. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum.

- ^ "Search result". Vincent van Gogh. The Letters. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum.

- ^ "Letter 686 note 21". Vincent van Gogh. The Letters. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum.

- ^ 'Utagawa, Japonaiserie and Vincent Van Gogh' in: Forbes, Andrew; Henley, David (2014). 100 Famous Views of Edo. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B00HR3RHUY

- ^ "The Feast of Seven Herbs (Imayo musume nanakusa)". State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Opening Night in the Theater District for Two Theaters of Edo (Edo ryôza Shibai-machi kaomise no zu)". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "No 17 Yui, Satta-mine 由井薩埵嶺 (Yui: Satta Peak) / Tokaido gojusan-tsugi no uchi 東海道五拾三次之内 (Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido Highway)". British Museum. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Ando Hiroshige". Hiroshige.org. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "The Actors Nakamura Wadaemon and Nakamura Konoz". British Museum. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Utamaro: Women sewing". British Museum. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Houses Seen from the Back". Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Courtesan (after Eisen)". Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Bridge in the Rain (after Hiroshige)". Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Flowering Plum Orchard (after Hiroshige)". Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Sprig of Flowering Almond in a Glass". Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "The Bedroom". Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Fishing Boats on the Beach at Les Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer". Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "The Rock of Montmajour with Pine Trees". Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "The Langlois Bridge". Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "The Harvest". Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "The Sower". Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Almond Blossom". Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

External links[edit]

- Krikke, Jan. "Vincent van Gogh: Lessons from Japan". The Vincent van Gogh Gallery. Retrieved 2010-08-25.

- "Japonism". Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

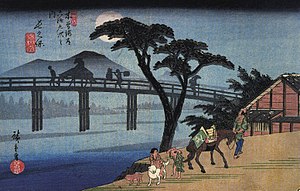

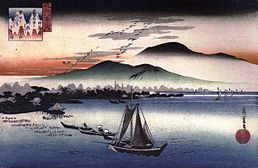

Utagawa Hiroshige (Japanese: 歌川 広重), also Andō Hiroshige (Japanese: 安藤 広重; 1797 – 12 October 1858), was a Japanese ukiyo-e artist, considered the last great master of that tradition.

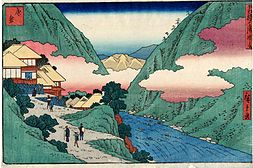

Hiroshige is best known for his landscapes, such as the series The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō and The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kiso Kaidō; and for his depictions of birds and flowers. The subjects of his work were atypical of the ukiyo-e genre, whose typical focus was on beautiful women, popular actors, and other scenes of the urban pleasure districts of Japan's Edo period (1603–1868). The popular Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series by Hokusai was a strong influence on Hiroshige's choice of subject, though Hiroshige's approach was more poetic and ambient than Hokusai's bolder, more formal prints.

For scholars and collectors, Hiroshige's death marked the beginning of a rapid decline in the ukiyo-e genre, especially in the face of the westernization that followed the Meiji Restoration of 1868. Hiroshige's work came to have a marked influence on Western painting towards the close of the 19th century as a part of the trend in Japonism. Western artists closely studied Hiroshige's compositions, and some, such as van Gogh, painted copies of Hiroshige's prints.

Contents

[hide]Early life and apprenticeship[edit]

Hiroshige was born in 1797 in the Yayosu Quay section of the Yaesu area in Edo (modern Tokyo).[1] He was of a samurai background,[1] and was the great-grandson of Tanaka Tokuemon, who held a position of power under the Tsugaru clan in the northern province of Mutsu. Hiroshige's grandfather, Mitsuemon, was an archery instructor who worked under the name Sairyūken. Hiroshige's father, Gen'emon, was adopted into the family of Andō Jūemon, whom he succeeded as fire warden for the Yayosu Quay area.[1]

Hiroshige went through several name changes as a youth: Jūemon, Tokubē, and Tetsuzō.[1] He had three sisters, one of whom died when he was three. His mother died in early 1809, and his father followed later in the year, but not before handing his fire warden duties to his twelve-year-old son.[2] He was charged with prevention of fires at Edo Castle, a duty that left him much leisure time.[3]

Not long after his parents' deaths, perhaps at around fourteen, Hiroshige—then named Tokutarō— began painting.[2] He sought the tutelage of Toyokuni of the Utagawa school, but Toyokuni had too many pupils to make room for him.[3] A librarian introduced him instead to Toyohiro of the same school.[4] By 1812 Hiroshige was permitted to sign his works, which he did under the art name Hiroshige.[2] He also studied the techniques of the well-established Kanō school, the nanga whose tradition began with the Chinese Southern School, and the realistic Shijō school, and likely the perspective techniques of Western art and uki-e.[5]

Hiroshige's apprentice work included book illustrations and single-sheet ukiyo-e prints of female beauties and kabuki actors in the Utagawa style, sometimes signing them Ichiyūsai[6] or, from 1832, Ichiryūsai.[7] In 1823, he resigned his post as fire warden, though he still acted as an alternate.[a] He declined an offer to succeed Toyohiro upon the master's death in 1828.[3]

Landscapes, flora, and fauna[edit]

It was not until 1829–1830 that Hiroshige began to produce the landscapes he has come to be known for, such as the Eight Views of Ōmi series.[8] He also created an increasing number of bird and flower prints about this time.[7] About 1831, his Ten Famous Places in the Eastern Capital appeared, and seem to bear the influence of Hokusai, whose popular landscape series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji had recently seen publication.[9]

An invitation to join an official procession to Kyoto in 1832 gave Hiroshige the opportunity to travel along the Tōkaidō route that linked the two capitals. He sketched the scenery along the way, and when he returned to Edo he produced the series The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō, which contains some of his best-known prints.[9] Hiroshige built on the series' success by following it with others, such as the Illustrated Places of Naniwa (1834), Famous Places of Kyoto (1835), another Eight Views of Ōmi (1834). As he had never been west of Kyoto, Hiroshige-based his illustrations of Naniwa (modern Osaka) and Ōmi Province on pictures found in books and paintings.[10]

- Selections from ''The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō''

Hiroshige's first wife helped finance his trips to sketch travel locations, in one instance selling some of her clothing and ornamental combs. She died in October 1838, and Hiroshige remarried to Oyasu,[b] sixteen years his junior, daughter of a farmer named Kaemon from Tōtōmi Province.[11]

Around 1838 Hiroshige produced two series entitled Eight Views of the Edo Environs, each print accompanied by a humorous kyōka poem. The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kiso Kaidō saw print between about 1835 and 1842, a joint production with Keisai Eisen, of which Hiroshige's share was forty-six of the seventy prints.[12] Hiroshige produced 118 sheets for the One Hundred Famous Views of Edo[13] over the last decade of his life, beginning about 1848.[14]

- Selections from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo and Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji

Hiroshige lived in the barracks until the age of 43. Gen'emon and his wife died in 1809, when Hiroshige was 12 years old, just a few months after his father had passed the position on to him. Although his duties as a fire-fighter were light, he never shirked these responsibilities, even after he entered training in Utagawa Toyohiro's studio. He eventually turned his firefighter position over to his brother, Tetsuzo, in 1823, who in turn passed on the duty to Hiroshige's son in 1832.

Hiroshige's students[edit]

Hiroshige II was a young print artist, Chinpei Suzuki, who married Hiroshige's daughter, Otatsu. He was given the artist name of "Shigenobu". Hiroshige intended to make Shigenobu his heir in all matters, and Shigenobu adopted the name "Hiroshige" after his master's death in 1858, and thus today is known as Hiroshige II. However, the marriage to Otatsu was troubled and in 1865 they separated. Otatsu was remarried to another former pupil of Hiroshige, Shigemasa, who appropriated the name of the lineage and today is known as Hiroshige III. Both Hiroshige II and Hiroshige III worked in a distinctive style based on that of Hiroshige, but neither achieved the level of success and recognition accorded to their master. Other students of Hiroshige I include Utagawa Shigemaru, Utagawa Shigekiyo, and Utagawa Hirokage.

- Followers of Hiroshige

Late life[edit]

In his declining years, Hiroshige still produced thousands of prints to meet the demand for his works, but few were as good as those of his early and middle periods. He never lived in financial comfort, even in old age. In no small part, his prolific output stemmed from the fact that he was poorly paid per series, although he was still capable of remarkable art when the conditions were right — his great One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (名所江戸百景 Meisho Edo Hyakkei) was paid for up-front by a wealthy Buddhist priest in love with the daughter of the publisher, Uoya Eikichi (a former fishmonger).

In 1856, Hiroshige "retired from the world," becoming a Buddhist monk; this was the year he began his One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. He died aged 62 during the great Edo cholera epidemic of 1858 (whether the epidemic killed him is unknown) and was buried in a Zen Buddhist temple in Asakusa. Just before his death, he left a poem:

- "I leave my brush in the East

- And set forth on my journey.

- I shall see the famous places in the Western Land."

(The Western Land in this context refers to the strip of land by the Tōkaidō between Kyoto and Edo, but it does double duty as a reference to the paradise of the Amida Buddha).

Despite his productivity and popularity, Hiroshige was not wealthy—his commissions were less than those of other in-demand artists, amounting to an income of about twice the wages of a day labourer. His will left instructions for the payment of his debts.[15]

Works[edit]

Hiroshige produced over 8,000 works.[17] He largely confined himself in his early work to common ukiyo-e themes such as women (美人画 bijin-ga) and actors (役者絵 yakusha-e). Then, after the death of Toyohiro, Hiroshige made a dramatic turnabout, with the 1831 landscape series Famous Views of the Eastern Capital (東都名所 Tōto Meisho) which was critically acclaimed for its composition and colors. This set is generally distinguished from Hiroshige's many print sets depicting Edo by referring to it as Ichiyūsai Gakki, a title derived from the fact that he signed it as Ichiyūsai Hiroshige. With The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō (1833–1834), his success was assured.[13] These designs were drawn from Hiroshige's actual travels of the full distance of 490 kilometers (300 mi). They included details of date, location, and anecdotes of his fellow travelers, and were immensely popular. In fact, this series was so popular that he reissued it in three versions, one of which was made jointly with Kunisada.[18] Hiroshige went on to produce more than 2000 different prints of Edo and post stations Tōkaidō, as well as series such as The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kisokaidō (1834–1842) and his own Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (1852–1858).[13] Of his estimated total of 5000 designs, these landscapes comprised the largest proportion of any genre.

He dominated landscape printmaking with his unique brand of intimate, almost small-scale works compared against the older traditions of landscape painting descended from Chinese landscape painters such as Sesshu. The travel prints generally depict travelers along famous routes experiencing the special attractions of various stops along the way. They travel in the rain, in snow, and during all of the seasons. In 1856, working with the publisher Uoya Eikichi, he created a series of luxury edition prints, made with the finest printing techniques including true gradation of color, the addition of mica to lend a unique iridescent effect, embossing, fabric printing, blind printing, and the use of glue printing (wherein ink is mixed with glue for a glittery effect). Hiroshige pioneered the use of the vertical format in landscape printing in his series Famous Views of the Sixty-odd Provinces. One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (issued serially between 1856 and 1859) was immensely popular. The set was published posthumously and some prints had not been completed — he had created over 100 on his own, but two were added by Hiroshige II after his death.

Influence[edit]

Hiroshige was a member of the Utagawa school, along with Kunisada and Kuniyoshi. The Utagawa school comprised dozens of artists, and stood at the forefront of 19th century woodblock prints. Particularly noteworthy for their actor and historical prints, members of the Utagawa school were nonetheless well-versed in all of the popular genres.

During Hiroshige’s time, the print industry was booming, and the consumer audience for prints was growing rapidly. Prior to this time, most print series had been issued in small sets, such as ten or twelve designs per series. Increasingly large series were produced to meet demand, and this trend can be seen in Hiroshige’s work, such as The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kisokaidō and One Hundred Famous Views of Edo.

In terms of style, Hiroshige is especially noted for using unusual vantage points, seasonal allusions, and striking colors. In particular, he worked extensively within the realm of meisho-e (名所絵) pictures of famous places. During the Edo period, tourism was also booming, leading to increased popular interest in travel. Travel guides abounded, and towns appeared along routes such as the Tōkaidō, a road that connected Edo with Kyoto. In the midst of this burgeoning travel culture, Hiroshige drew upon his own travels, as well as tales of others’ adventures, for inspiration in creating his landscapes. For example, in The Fifty-three Stations on the Tōkaidō (1833), he illustrates anecdotes from Travels on the Eastern Seaboard (東海道中膝栗毛 Tōkaidōchū Hizakurige, 1802–1809) by Jippensha Ikku, a comedy describing the adventures of two bumbling travelers as they make their way along the same road.

Hiroshige’s The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō (1833–1834) and One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (1856–1858) greatly influenced French Impressionists such as Monet. Vincent van Gogh copied two of the One Hundred Famous Views of Edo which were among his collection of ukiyo-e prints. Hiroshige's style also influenced the Mir iskusstva, a 20th-century Russian art movement in which Ivan Bilibin was a major artist.[citation needed] Cézanne and Whistler were also amongst those under Hiroshige's influence.[19] Hiroshige was regarded by Louise Gonse, director of the influential Gazette des Beaux-Arts and author of the two volume L'Art Japonais in 1883, as the greatest painter of landscapes of the 19th century.[20]

- Van Gogh copies of Hiroshige's prints

Gallery[edit]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Hiroshige's resignation has led to conjecture: nominally, he passed the position to his son Nakajirō, but it may have been that Nakajirō was actually the son of his adoptive grandfather. Hiroshige, as adopted heir, may have been made to give up the position to the purported legitimate heir.[3]

- ^ When Hiroshige and Oyasu married is not known.[11]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c d Oka 1992, p. 69.

- ^ a b c Oka 1992, p. 70.

- ^ a b c d Oka 1992, p. 71.

- ^ Oka 1992, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Oka 1992, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Oka 1992, pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b Oka 1992, p. 74.

- ^ Oka 1992, pp. 73–74.

- ^ a b Oka 1992, p. 75.

- ^ Oka 1992, p. 79.

- ^ a b Noguchi 1992, p. 177.

- ^ Oka 1992, p. 81.

- ^ a b c Forbes & Henley (2014). Full series

- ^ Oka 1992, p. 83.

- ^ Oka 1992, p. 68.

- ^ "Kisokaido Road". Hiroshige. Retrieved 2011-12-26.

- ^ Oka 1992, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Christine Guth, Art of Edo Japan: The Artist and the City, 1615–1868 (Harry Abrams, 1996). ISBN 0-8109-2730-6

- ^ Oka 1992, p. 67.

- ^ G.P. Weisberg; P.D. Cate; G. Needham; M. Eidelberg; W.R. Johnston. Japonisme - Japanese Influence on French Art 1854-1910. London: Cleveland Museum of Art, Walters Art Gallery, Robert G. Sawyers Publications. ISBN 0-910386-22-6.

Works cited[edit]

- Forbes, Andrew; Henley, David (2014). 100 Famous Views of Edo. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B00HR3RHUY

- Forbes, Andrew; Henley, David (2014). Utagawa Hiroshige’s 36 Views of Mount Fuji. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B00KD7CZ9O

- Forbes, Andrew; Henley, David (2014). Utagawa Hiroshige's 53 Stations of the Tokaido. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B00LM4APAI

- Noguchi, Yoné (1992). Selected English Writings of Yone Noguchi: Prose. Associated University Presse. ISBN 978-0-8386-3422-6.

- Oka, Isaburo (1992). Hiroshige: Japan's Great Landscape Artist. Kodansha. ISBN 9784770016584.

Further reading[edit]

- Hiroshige: one Hundred Famous Views of Edo (1986). Smith II, Henry D.; Poster, G Amy; Lehman, L. Arnold. Publisher: George Braziller Inc, plates from the Brooklyn Museum. Paperback: ISBN 0-87273-141-3; hardcover: ISBN 0-8076-1143-3

- Ukiyo-e: 250 years of Japanese Art (1979). Toni Neuer, Herbert Libertson, Susugu Yoshida; W. H. Smith. ISBN 0-8317-9041-5

- Friese, Gordon: Keisai Eisen - Utugawa Hiroshige. Die 69 Stationen des Kisokaidô. Eine vollständige Serie japanischer Farbholzschnitte und ihre Druckvarianten. Verlag im Bücherzentrum, Germany, Unna 2008. ISBN 978-3-9809261-3-3

- Tom Rassieur, 'Degas and Hiroshige', Print Quarterly XXVIII, 2011, pp. 429–31

- Calza, Gian Carlo (2009). Hiroshige: The Master of Nature. Skira. ISBN 978-88-572-0106-1.

- Uspensky, Mikhail (2011). Hiroshige. Parkstone International. ISBN 978-1-78042-183-4.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Utagawa Hiroshige. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Hiroshige. |

- Shizuoka City Tokaido Hiroshige Museum of Art (in Japanese)

- Ando Hiroshige Catalogue

- Ukiyo-e Prints by Utagawa Hiroshige

- Brooklyn Museum: Exhibitions: one Hundred Famous Views of Edo

- Hiroshige's works at Tokyo Digital Museum