The Tale of Genji, by Murasaki Shikibu

Table of Contents

- The Paulownia Court

- The Broom Tree

- The Shell of the Locust

- Evening Faces

- Lavender

- The Safflower

- An Autumn Exersion

- The Festival of the Cherry Blossoms

- Heartvine

- The Sacred Tree

- The Orange Blossoms

- Suma

- Akashi

- Channel Buoys

- The Wormwood Patch

- The Gatehouse

- A Picture Contest

- The Wind in the Pines

- A Rack of Cloud

- The Morning Glory

- The Maiden

- The Jeweled Chaplet

- The First Warbler

- Butterflies

- Fireflies

- Wild Carnations

- Flares

- The Typhoon

- The Royal Outing

- Purple Trousers

- The Cypress Pillar

- A Branch of Plum

- Wisteria Leaves

- New Herbs

- New Herbs

- The Oak Tree

- The Flute

- The Bell Cricket

- Evening Mist

- The Rites

- The Wizard

- His Perfumed Highness

- The Rose Plum

- Bamboo River

- The Lady at the Bridge

- Beneath the Oak

- Trefoil Knots

- Early Ferns

- The Ivy

- The Eastern Cottage

- A Boat upon the Waters

- The Drake Fly

- The Writing Practice

- The Floating Bridge of Dreams

무라사키 시키부

일본 문학의 최고봉 『원씨물어』의 저자

[ 紫式部 ]생애

무라사키 시키부는 하급 관료인 아버지 후지와라노 타메토키의 딸로, 역사상 가장 오래된 소설 중 하나인 『원씨물어(源氏物語)』의 저자이다. 어머니는 하급 관료인 후지와라노 타메노부의 딸이다. 어려서 어머니를 여의고 지방관이었던 아버지의 임지를 따라 이동하며 생활했는데, 학자이기도 한 아버지에게 한학을 배웠다. 생몰연도가 명확하지는 않으나 대체로 970년에서 973년 사이에 태어나서 1014년에서 1025년 사이에 사망했다고 보고 있다.

집안이 후지와라 가문이고 아버지가 관직을 역임한 것으로 보아, 당시에는 토우노 시키부(藤式部)라고 불렸을 것으로 보인다. ‘무라사키 시키부’라는 이름은 사후에 붙여진 것으로, ‘무라사키’는 『원씨물어』의 여주인공 무라사키노 우에에서 유래했다. 그리고 ‘시키부’는 아버지의 관직명, 즉 대학료를 통괄하는 식무성의 식무대승이라는 명칭에서 유래했다고 한다.

당시에는 귀족의 자녀일지라도 여자일 경우 가나(문자)와 와카(일본 고유 형식의 시) 정도만 교육시키는 것이 일반적이었다. 그러나 딸의 재능을 알아본 아버지는 무라사키에게 한문까지도 가르쳤다. 그녀는 998년에 나이 차가 상당한 지방관 후지와라노 노부타카와 결혼하여 슬하에 1녀를 두었다. 그러나 결혼한 지 3년 만인 1001년에 당시 유행하던 전염병으로 인해 남편이 사망했다. 여러 이유로 그녀의 결혼생활은 원만하지 못했는데, 남편과의 부부싸움을 노래로 읊은 것이 지금까지 전해지고 있다.

남편과 사별한 이후 무라사키는 『원씨물어』를 집필하기 시작했다. 이 작품에 대한 평가가 높아서 1005년에 이치조 천황의 부인인 후지와라노 쇼시의 가정교사 일을 시작하여 대체로 1018년까지 지속했다고 한다. 무라사키의 남편은 노부타카라고 하는 것이 통설이다. 그러나 이론도 상당히 존재한다. 예를 들어 『권기(権記)』의 기록에 의거하여 노부타카와 결혼하기 전에 키노 토키부미와 결혼했다고 하는 주장도 있다. 또한 가마쿠라 시대 공가(조정의 귀족)의 계보를 집대성한 『존비분맥(尊卑分脈)』에 의하면, 그녀가 후지와라노 미치나가의 첩이었다는 기록도 있다.

어린 시절 무라사키는 밝고 쾌활한 성격의 소유자였다. 그러나 남편의 이른 죽음으로 인한 결혼생활의 마감, 중류 귀족 신분의 미망인으로서 궁중에 들어가 황족의 시중을 드는 궁중생활, 뛰어난 재능을 가지고 있음에도 여성이라는 이유로 이를 드러낼 수 없었던 시대적 환경 등으로 인해 그녀의 성격은 점차 내성적으로 바뀌었다고 한다. 이 때문에 그녀는 병풍에 있는 한시를 읽을 수 있음에도 모른다고 한다거나 나라(奈良) 지역에서 보낸 벚꽃을 수령하는 역할을 남자인 다른 사람에게 양보하는 등 사람들의 눈에 띄지 않으려는 행동을 했다고 한다.

그녀의 작품집으로 『원씨물어』, 『무라사키 시키부 일기(紫式部日記)』, 『무라사키 시키부집(紫式部集)』이 있고, 그 외 『후습유화가집(後拾遺和歌集)』에 다수의 시가 수록되어 있다. 『무라사키 시키부 일기』는 후궁의 영화를 침울한 자신의 마음에 빗대어 기록한 서간문에 비평을 곁들인 형식의 작품이다. 한편 『원씨물어』는 사본과 판본에 따라 조금씩 다르지만 통상 54첩으로 이루어져 있으며, 500여 명의 등장인물과 70여 년간 일어난 여러 사건을 묘사한 장편의 궁중 이야기이다.

작품의 구성과 묘사에서 중국문학 속에 전하는 여러 전승과 역사적 사실을 다양하게 활용하고, 이전에 이루어진 많은 작품을 계승하여 시와 산문을 융합한 형식을 만들면서도 인간의 내면세계에 대한 뛰어난 묘사를 이루어내는 등 형식과 내용면에서 새로운 수준에 달한 문학작품으로 평가받고 있다. 옛날의 문학작품에는 전체적 내용을 통괄할 수 있는 제목이 명기된 것이 그리 많지 않고 오히려 각각의 첩의 내용을 나타내는 소제목을 나타내는 것이 많았다.

이러한 연유로 이 작품 역시 당시의 원제목이 무엇이었는지는 명확하지 않다. 다만, 문헌에 전하는 예를 보면, 「원씨의 이야기」, 「빛나는 원씨의 이야기」, 「빛나는 원씨의 이야기」, 「빛나는 원씨」, 「원씨」, 「원씨의 군(君)」, 「무라사키의 이야기」, 「무라사키의 관계」, 「무라사키의 관계 이야기」 등의 제목이 보인다.

이 작품은 모계제가 강하게 유지되고 있던 헤이안 시대를 배경으로 원래는 천황의 친왕 신분이었으나 신분이 신하로 강등되어 원씨가 된 집안의 영광과 고뇌, 그 자손들의 삶의 역정을 그렸다. 통상 이 작품은 3부로 구성되어 있다. 1부는 원씨가 많은 연애 행각을 펼치면서 황실 가문의 인물로서 최고의 영예를 누리는 인생의 전반부, 2부는 애정 행각의 파탄에 따른 무상과 허탈, 그리고 출가를 지향하는 인생 후반부, 3부는 원씨가 죽고 난 이후 자녀들의 삶과 사랑의 모습이 묘사되어 있다. 헤이안 시대의 일본문학을 『원씨물어』를 전후하여 전기와 후기로 구분하거나 혹은 『원씨물어』만을 헤이안 중기의 문학으로 구분하는 설도 있다.

연관 표제어

참고문헌

- デジタル大辞泉

- 百科事典マイペディア

- 朝日日本歴史人物事典

- デジタル大辞泉プラス

- 世界大百科事典 第2版

- 大辞林 第三版

- ブリタニカ国際大百科事典 小項目事典

- 日本大百科全書

- デジタル版日本人名大辞典+Plus

- 日本古代中世人名辞典

[네이버 지식백과] 무라사키 시키부 [紫式部] - 일본 문학의 최고봉 『원씨물어』의 저자 (일본 문화예술인, 세손출판사, 일본사학회)

Murasaki Shikibu (紫 式部?, English: Lady Murasaki; c. 973 or 978 – c. 1014 or 1031) was a Japanese novelist, poet and lady-in-waiting at the Imperial court during the Heian period. She is best known as the author of The Tale of Genji, written in Japanese between about 1000 and 1012. Murasaki Shikibu is a descriptive name; her personal name is unknown, but she may have been Fujiwara no Takako (藤原 香子?), who was mentioned in a 1007 court diary as an imperial lady-in-waiting.

Heian women were traditionally excluded from learning Chinese, the written language of government, but Murasaki, raised in her erudite father's household, showed a precocious aptitude for the Chinese classics and managed to acquire fluency. She married in her mid-to late twenties and gave birth to a daughter before her husband died, two years after they were married. It is uncertain when she began to write The Tale of Genji, but it was probably while she was married or shortly after she was widowed. In about 1005, Murasaki was invited to serve as a lady-in-waiting to Empress Shōshi at the Imperial court, probably because of her reputation as a writer. She continued to write during her service, adding scenes from court life to her work. After five or six years, she left court and retired with Shōshi to the Lake Biwa region. Scholars differ on the year of her death; although most agree on 1014, others have suggested she was alive in 1031.

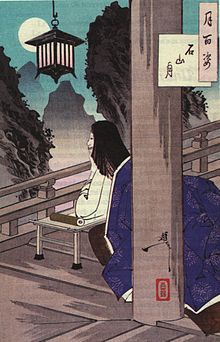

Murasaki wrote The Diary of Lady Murasaki, a volume of poetry, and The Tale of Genji. Within a decade of its completion, Genji was distributed throughout the provinces; within a century it was recognized as a classic of Japanese literature and had become a subject of scholarly criticism. Early in the 20th century her work was translated; a six-volume English translation was completed in 1933. Scholars continue to recognize the importance of her work, which reflects Heian court society at its peak. Since the 13th century her works have been illustrated by Japanese artists and well-known ukiyo-e woodblock masters.

Contents

[hide]Early life[edit]

Murasaki Shikibu was born c. 973[1] in Heian-kyō, Japan, into the northern Fujiwara clan descending from Fujiwara no Yoshifusa, the first 9th-century Fujiwara regent.[2] The Fujiwara clan dominated court politics until the end of the 11th century through strategic marriages of Fujiwara daughters into the imperial family and the use of regencies. In the late 10th century and early 11th century, Fujiwara no Michinaga arranged his four daughters into marriages with emperors, giving him unprecedented power.[3] Murasaki's great-grandfather, Fujiwara no Kanesuke, had been in the top tier of the aristocracy, but her branch of the family gradually lost power and by the time of Murasaki's birth was at the middle to lower ranks of the Heian aristocracy—the level of provincial governors.[4] The lower ranks of the nobility were typically posted away from court to undesirable positions in the provinces, exiled from the centralized power and court in Kyoto.[5]

Despite the loss of status, the family had a reputation among the literati through Murasaki's paternal great-grandfather and grandfather, both of whom were well-known poets. Her great-grandfather, Fujiwara no Kanesuke, had fifty-six poems included in thirteen of the Twenty-one Imperial Anthologies,[6] the Collections of Thirty-six Poets and the Yamato Monogatari (Tales of Yamato).[7] Her great-grandfather and grandfather both had been friendly with Ki no Tsurayuki, who became notable for popularizing verse written in Japanese.[5] Her father, Fujiwara no Tametoki, attended the State Academy (Daigaku-ryō)[8] and became a well-respected scholar of Chinese classics and poetry; his own verse was anthologized.[9] He entered public service around 968 as a minor official and was given a governorship in 996. He stayed in service until about 1018.[5][10] Murasaki's mother was descended from the same branch of northern Fujiwara as Tametoki. The couple had three children, a son and two daughters.[9]

In the Heian era the use of names, insofar as they were recorded, did not follow a modern pattern. A court lady, as well as being known by the title of her own position, if any, took a name referring to the rank or title of a male relative. Thus "Shikibu" is not a modern surname, but refers to Shikibu-shō, the Ministry of Ceremonials where Murasaki's father was a functionary. "Murasaki", an additional name possibly derived from the color violet associated with wisteria, the meaning of the word fuji (an element of her clan name), may have been bestowed on her at court in reference to the name she herself had given to the main female character in "Genji". Michinaga mentions the names of several ladies-in-waiting in a 1007 diary entry; one, Fujiwara no Takako (Kyōshi), may be Murasaki's personal name.[7][11]

In Heian-era Japan, husbands and wives kept separate households; children were raised with their mothers, although the patrilineal system was still followed.[12]Murasaki was unconventional because she lived in her father's household, most likely on Teramachi Street in Kyoto, with her younger brother Nobunori. Their mother died, perhaps in childbirth, when the children were quite young. Murasaki had at least three half-siblings raised with their mothers; she was very close to one sister who died in her twenties.[13][14][15]

Murasaki was born at a period when Japan was becoming more isolated, after missions to China had ended and a stronger national culture was emerging.[16] In the 9th and 10th centuries, Japanese gradually became a written language through the development of kana, a syllabary based on abbreviations of Chinese characters. In Murasaki's lifetime men continued to write in Chinese, the language of government, but kana became the written language of noblewomen, setting the foundation for unique forms of Japanese literature.[17]

Chinese was taught to Murasaki's brother as preparation for a career in government, and during her childhood, living in her father's household, she learned and became proficient in classical Chinese.[8] In her diary she wrote, "When my brother ... was a young boy learning the Chinese classics, I was in the habit of listening to him and I became unusually proficient at understanding those passages that he found too difficult to understand and memorize. Father, a most learned man, was always regretting the fact: 'Just my luck,' he would say, 'What a pity she was not born a man!'"[18] With her brother she studied Chinese literature, and she probably also received instruction in more traditional subjects such as music, calligraphy and Japanese poetry.[13] Murasaki's education was unorthodox. Louis Perez explains in The History of Japan that "Women ... were thought to be incapable of real intelligence and therefore were not educated in Chinese."[19] Murasaki was aware that others saw her as "pretentious, awkward, difficult to approach, prickly, too fond of her tales, haughty, prone to versifying, disdainful, cantankerous and scornful".[20] Asian literature scholar Thomas Inge believes she had "a forceful personality that seldom won her friends".[8]

Marriage[edit]

Aristocratic Heian women lived restricted and secluded lives, allowed to speak to men only when they were close relatives or household members. Murasaki's autobiographical poetry shows that she socialized with women but had limited contact with men other than her father and brother; she often exchanged poetry with women but never with men.[13] Unlike most noblewomen of her status, she did not marry on reaching puberty; instead she stayed in her father's household until her mid-twenties or perhaps even to her early thirties.[13][21]

In 996 when her father was posted to a four-year governorship in Echizen Province, Murasaki went with him, although it was uncommon for a noblewoman of the period to travel such a distance on a trip that could take as long as five days.[22] She returned to Kyoto, probably in 998, to marry her father's friend Fujiwara no Nobutaka (c. 950 – c. 1001), a much older second cousin.[5][13] Descended from the same branch of the Fujiwara clan, he was a court functionary and bureaucrat at the Ministry of Ceremonials, with a reputation for dressing extravagantly and as a talented dancer.[22] In his late forties at the time of their marriage, he had multiple households with an unknown number of wives and offspring.[7] Gregarious and well known at court, he was involved in numerous romantic relationships that may have continued after his marriage to Murasaki.[13] As was customary, she would have remained in her father's household where her husband would have visited her.[7] Nobutaka had been granted more than one governorship, and by the time of his marriage to Murasaki he was probably quite wealthy. Accounts of their marriage vary: Richard Bowring writes that the marriage was happy, but Japanese literature scholar Haruo Shirane sees indications in her poems that she resented her husband.[5][13]

The couple's daughter, Kenshi (Kataiko), was born in 999. Two years later Nobutaka died during a cholera epidemic.[13] As a married woman Murasaki would have had servants to run the household and care for her daughter, giving her ample leisure time. She enjoyed reading and had access to romances (monogatari) such as The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter and The Tales of Ise.[22] Scholars believe she may have started writing The Tale of Genji before her husband's death; it is known she was writing after she was widowed, perhaps in a state of grief.[2][5] In her diary she describes her feelings after her husband's death: "I felt depressed and confused. For some years I had existed from day to day in listless fashion ... doing little more than registering the passage of time ... The thought of my continuing loneliness was quite unbearable".[23]

According to legend, Murasaki retreated to Ishiyama-dera at Lake Biwa, where she was inspired to write The Tale of Genji on an August night while looking at the moon. Although scholars dismiss the factual basis of the story of her retreat, Japanese artists often depicted her at Ishiyama Temple staring at the moon for inspiration.[14] She may have been commissioned to write the story and may have known an exiled courtier in a similar position to her hero Prince Genji.[24] Murasaki would have distributed newly written chapters of Genji to friends who in turn would have re-copied them and passed them on. By this practice the story became known and she gained a reputation as an author.[25]

In her early to mid-thirties, she became a lady-in-waiting (nyōbō) at court, most likely because of her reputation as an author.[2][25] Chieko Mulhern writes in Japanese Women Writers, a Biocritical Sourcebook that scholars have wondered why Murasaki made such a move at a comparatively late period in her life. Her diary evidences that she exchanged poetry with Michinaga after her husband's death, leading to speculation that the two may have been lovers. Bowring sees no evidence that she was brought to court as Michinaga's concubine, although he did bring her to court without following official channels. Mulhern thinks Michinaga wanted to have Murasaki at court to educate his daughter Shōshi.[26]

Court life[edit]

Heian culture and court life reached a peak early in the 11th century.[3] The population of Kyoto grew to around 100,000 as the nobility became increasingly isolated at the Heian Palace in government posts and court service.[27] Courtiers became overly refined with little to do, insulated from reality, preoccupied with the minutiae of court life, turning to artistic endeavors.[3][27] Emotions were commonly expressed through the artistic use of textiles, fragrances, calligraphy, colored paper, poetry, and layering of clothing in pleasing color combinations—according to mood and season. Those who showed an inability to follow conventional aesthetics quickly lost popularity, particularly at court.[19] Popular pastimes for Heian noblewomen—who adhered to rigid fashions of floor-length hair, whitened skin and blackened teeth—included having love affairs, writing poetry and keeping diaries. The literature that Heian court women wrote is recognized as some of the earliest and among the best literature written in the Japanese canon.[3][27]

Rival courts and women poets[edit]

When in 995 Michinaga's two brothers Fujiwara no Michitaka and Fujiwara no Michikane died leaving the regency vacant, Michinaga quickly won a power struggle against his nephew Fujiwara no Korechika (brother to Teishi, Emperor Ichijō's wife), and, aided by his sister Senshi, he assumed power. Teishi had supported her brother Korechika, who was later discredited and banished from court, causing her to lose power.[28] Four years later Michinaga sent Shōshi, his eldest daughter, to Emperor Ichijō's harem when she was about 12.[29] A year after placing Shōshi in the imperial harem, in an effort to undermine Teishi's influence and increase Shōshi's standing, Michinaga had her named Empress although Teishi already held the title. As historian Donald Shively explains, "Michinaga shocked even his admirers by arranging for the unprecedented appointment of Teishi (or Sadako) and Shōshi as concurrent empresses of the same emperor, Teishi holding the usual title of "Lustrous Heir-bearer" kōgō and Shōshi that of "Inner Palatine" (chūgū), a toponymically derived equivalent coined for the occasion".[28] About five years later, Michinaga brought Murasaki to Shōshi's court, in a position that Bowring describes as a companion-tutor.[30]

Women of high status lived in seclusion at court and, through strategic marriages, were used to gain political power for their families. Despite their seclusion, some women wielded considerable influence, often achieved through competitive salons, dependent on the quality of those attending.[31] Ichijō's mother and Michinaga's sister, Senshi, had an influential salon, and Michinaga probably wanted Shōshi to surround herself with skilled women such as Murasaki to build a rival salon.[25]

Shōshi was 16 to 19 when Murasaki joined her court.[32] According to Arthur Waley, Shōshi was a serious-minded young lady, whose living arrangements were divided between her father's household and her court at the Imperial Palace.[33] She gathered around her talented women writers such as Izumi Shikibu and Akazome Emon—the author of an early vernacular history, The Tale of Flowering Fortunes.[34] The rivalry that existed among the women is evident in Murasaki's diary, where she wrote disparagingly of Izumi: "Izumi Shikibu is an amusing letter-writer; but there is something not very satisfactory about her. She has a gift for dashing off informal compositions in a careless running-hand; but in poetry she needs either an interesting subject or some classic model to imitate. Indeed it does not seem to me that in herself she is really a poet at all."[35]

Sei Shōnagon, author of the The Pillow Book, had been in service as lady-in-waiting to Teishi when Shōshi came to court; it is possible that Murasaki was invited to Shōshi's court as a rival to Shōnagon. Teishi died in 1001, before Murasaki entered service with Shōshi, so the two writers were not there concurrently, but Murasaki, who wrote about Shōnagon in her diary, certainly knew of her, and to an extent was influenced by her.[36] Shōnagon's The Pillow Book may have been commissioned as a type of propaganda to highlight Teishi's court, known for its educated ladies-in-waiting. Japanese literature scholar Joshua Mostow believes Michinaga provided Murasaki to Shōshi as an equally or better educated woman, so as to showcase Shōshi's court in a similar manner.[37]

The two writers had different temperaments: Shōnagon was witty, clever, and outspoken; Murasaki was withdrawn and sensitive. Entries in Murasaki's diary show that the two may not have been on good terms. Murasaki wrote, "Sei Shōnagon ... was dreadfully conceited. She thought herself so clever, littered her writing with Chinese characters, [which] left a great deal to be desired."[38] Keene thinks that Murasaki's impression of Shōnagon could have been influenced by Shōshi and the women at her court because Shōnagon served Shōshi's rival empress. Furthermore, he believes Murasaki was brought to court to write Genji in response to Shōnagon's popular Pillow Book.[36] Murasaki contrasted herself to Shōnagon in a variety of ways. She denigrated the pillow book genre and, unlike Shōnagon who flaunted her knowledge of Chinese, Murasaki pretended to not know the language.[37]

"The Lady of the Chronicles"[edit]

Although the popularity of the Chinese language diminished in the late Heian era, Chinese ballads continued to be popular, including those written by Bai Juyi. Murasaki taught Chinese to Shōshi who was interested in Chinese art and Juyi's ballads. Upon becoming Empress, Shōshi installed screens decorated with Chinese script, causing outrage because written Chinese was considered the language of men, far removed from the women's quarters.[39] The study of Chinese was thought to be unladylike and went against the notion that only men should have access to the literature. Women were supposed to read and write only in Japanese, which separated them through language from government and the power structure. Murasaki, with her unconventional classical Chinese education, was one of the few women available to teach Shōshi classical Chinese.[40] Bowring writes it was "almost subversive" that Murasaki knew Chinese and taught the language to Shōshi.[41] Murasaki, who was reticent about her Chinese education, held the lessons between the two women in secret, writing in her diary, "Since last summer ... very secretly, in odd moments when there happened to be no one about, I have been reading with Her Majesty ... There has of course been no question of formal lessons ... I have thought it best to say nothing about the matter to anybody."[42]

Murasaki probably earned an ambiguous nickname, "The Lady of the Chronicles" (Nihongi no tsubone), for teaching Shōshi Chinese literature.[25] A lady-in-waiting who disliked Murasaki accused her of flaunting her knowledge of Chinese and began calling her "The Lady of the Chronicles"—an allusion to the classic Chronicles of Japan—after an incident in which chapters from Genji were read aloud to the Emperor and his courtiers, one of whom remarked that the author showed a high level of education. Murasaki wrote in her diary, "How utterly ridiculous! Would I, who hesitate to reveal my learning to my women at home, ever think of doing so at court?"[43] Although the nickname was apparently meant to be disparaging, Mulhern believes Murasaki was flattered by it.[25]

The attitude toward the Chinese language was contradictory. In Teishi's court, Chinese had been flaunted and considered a symbol of imperial rule and superiority. Yet, in Shōshi's salon there was a great deal of hostility towards the language—perhaps owing to political expedience during a period when Chinese began to be rejected in favor of Japanese—even though Shōshi herself was a student of the language. The hostility may have affected Murasaki and her opinion of the court, and forced her to hide her knowledge of Chinese. Unlike Shōnagon, who was both ostentatious and flirtatious, as well as outspoken about her knowledge of Chinese, Murasaki seems to have been humble, an attitude which possibly impressed Michinaga. Although Murasaki used Chinese and incorporated it in her writing, she publicly rejected the language, a commendable attitude during a period of burgeoning Japanese culture.[44]

Murasaki seems to have been unhappy with court life and was withdrawn and somber. No surviving records show that she entered poetry competitions; she appears to have exchanged few poems or letters with other women during her service.[5] In general, unlike Sei Shōnagon, Murasaki gives the impression in her diary that she disliked court life, the other ladies-in-waiting, and the drunken revelry. She did, however, become close friends with a lady-in-waiting named Lady Saishō, and she wrote of the winters that she enjoyed, "I love to see the snow here".[45][46]

According to Waley, Murasaki may not have been unhappy with court life in general but bored in Shōshi's court. He speculates she would have preferred to serve with the Lady Senshi, whose household seems to have been less strict and more light-hearted. In her diary, Murasaki wrote about Shōshi's court, "[she] has gathered round her a number of very worthy young ladies ... Her Majesty is beginning to acquire more experience of life, and no longer judges others by the same rigid standards as before; but meanwhile her Court has gained a reputation for extreme dullness".[47]

Murasaki disliked the men at court whom she thought to be drunken and stupid. However, some scholars, such as Waley, are certain she was involved romantically with Michinaga. At the least, Michinaga pursued her and pressured her strongly, and her flirtation with him is recorded in her diary as late as 1010. Yet, she wrote to him in a poem, "You have neither read my book, nor won my love."[48] In her diary she records having to avoid advances from Michinaga—one night he sneaked into her room, stealing a newly written chapter of Genji.[49]However, Michinaga's patronage was essential if she was to continue writing.[50] Murasaki described his daughter's court activities: the lavish ceremonies, the complicated courtships, the "complexities of the marriage system",[21] and in elaborate detail, the birth of Shōshi's two sons.[49]

It is likely that Murasaki enjoyed writing in solitude.[49] She believed she did not fit well with the general atmosphere of the court, writing of herself: "I am wrapped up in the study of ancient stories ... living all the time in a poetical world of my own scarcely realizing the existence of other people .... But when they get to know me, they find to their extreme surprise that I am kind and gentle".[51] Inge says that she was too outspoken to make friends at court, and Mulhern thinks Murasaki's court life was comparatively quiet compared to other court poets.[8][25] Mulhern speculates that her remarks about Izumi were not so much directed at Izumi's poetry but at her behavior, lack of morality and her court liaisons, of which Murasaki disapproved.[34]

Rank was important in Heian court society and Murasaki would not have felt herself to have much, if anything, in common with the higher ranked and more powerful Fujiwaras.[52] In her diary, she wrote of her life at court: "I realized that my branch of the family was a very humble one; but the thought seldom troubled me, and I was in those days far indeed from the painful consciousness of inferiority which makes life at Court a continual torment to me."[53] A court position would have increased her social standing, but more importantly she gained a greater experience to write about.[25] Court life, as she experienced it, is well reflected in the chapters of Genji written after she joined Shōshi. The name Murasaki was most probably given to her at a court dinner in an incident she recorded in her diary: in c. 1008 the well-known court poet Fujiwara no Kintō inquired after the "Young Murasaki"—an allusion to the character named Murasaki in Genji—which would have been considered a compliment from a male court poet to a female author.[25]

Later life and death[edit]

When Emperor Ichijō died in 1011, Shōshi retired from the Imperial Palace to live in a Fujiwara mansion in Biwa, most likely accompanied by Murasaki, who is recorded as being there with Shōshi in 1013.[50] George Aston explains that when Murasaki retired from court she was again associated with Ishiyama-dera: "To this beautiful spot, it is said, Murasaki no Shikibu (sic) retired from court life to devote the remainder of her days to literature and religion. There are sceptics, however, Motoöri being one, who refuse to believe this story, pointing out ... that it is irreconcilable with known facts. on the other hand, the very chamber in the temple where the Genji was written is shown—with the ink-slab which the author used, and a Buddhist Sutra in her handwriting, which, if they do not satisfy the critic, still are sufficient to carry conviction to the minds of ordinary visitors to the temple."[54]

Murasaki may have died in 1014. Her father made a hasty return to Kyoto from his post at Echigo Province that year, possibly because of her death. Writing in A Bridge of Dreams: A Poetics of "The Tale of Genji", Shirane mentions that 1014 is generally accepted as the date of Murasaki Shikibu's death and 973 as the date of her birth, making her 41 when she died.[50] Bowring considers 1014 to be speculative, and believes she may have lived with Shōshi until as late as 1025.[55] Waley agrees given that Murasaki may have attended ceremonies with Shōshi held for her son, Emperor Go-Ichijō around 1025.[51]

Murasaki's brother Nubonori died in around 1011, which, combined with the death of his daughter, may have prompted her father to resign his post and take vows at Miidera temple where he died in 1029.[2][50] Murasaki's daughter entered court service in 1025 as a wet nurse to the future Emperor Go-Reizei (1025–68). She went on to become a well-known poet as Daini no Sanmi.[56]

Works[edit]

Three works are attributed to Murasaki: The Tale of Genji, The Diary of Lady Murasaki and Poetic Memoirs, a collection of 128 poems.[49] Her work is considered important because her writing reflects the creation and development of Japanese writing during a period when Japanese shifted from an unwritten vernacular to a written language.[31] Until the 9th century, Japanese language texts were written in Chinese characters using the man'yōgana writing system.[57] A revolutionary achievement was the development of kana, a true Japanese script, in the mid-to late 9th century. Japanese authors began to write prose in their own language, which led to genres such as tales (monogatari) and poetic journals (Nikki Bungaku).[58][59][60] Historian Edwin Reischauer writes that genres such as the monogatari were distinctly Japanese and that Genji, written in kana, "was the outstanding work of the period".[17]

Diary and poetry[edit]

Murasaki began her diary after she entered service at Shōshi's court.[49] Much of what we know about her and her experiences at court comes from the diary, which covers the period from about 1008 to 1010. The long descriptive passages, some of which may have originated as letters, cover her relationships with the other ladies-in-waiting, Michinaga's temperament, the birth of Shōshi's sons—at Michinaga's mansion rather than at the Imperial Palace—and the process of writing Genji, including descriptions of passing newly written chapters to calligraphers for transcriptions.[49][61] Typical of contemporary court diaries written to honor patrons, Murasaki devotes half to the birth of Shōshi's son Emperor Go-Ichijō, an event of enormous importance to Michinaga: he had planned for it with his daughter's marriage which made him grandfather and de facto regent to an emperor.[62]

Poetic Memoirs is a collection of 128 poems Mulhern describes as "arranged in a biographical sequence".[49] The original set has been lost. According to custom, the verses would have been passed from person to person and often copied. Some appear written for a lover—possibly her husband before he died—but she may have merely followed tradition and written simple love poems. They contain biographical details: she mentions a sister who died, the visit to Echizen province with her father and that she wrote poetry for Shōshi. Murasaki's poems were published in 1206 by Fujiwara no Teika, in what Mulhern believes to be the collection that is closest to the original form; at around the same time Teika included a selection of Murasaki's works in an imperial anthology, New Collections of Ancient and Modern Times.[49]

The Tale of Genji[edit]

Murasaki is best known for her The Tale of Genji, a three-part novel spanning 1100 pages and 54 chapters,[63][64] which is thought to have taken a decade to complete. The earliest chapters were possibly written for a private patron either during her marriage or shortly after her husband's death. She continued writing while at court and probably finished while still in service to Shōshi.[65] She would have needed patronage to produce a work of such length. Michinaga provided her with costly paper and ink, and with calligraphers. The first handwritten volumes were probably assembled and bound by ladies-in-waiting.[50]

In his The Pleasures of Japanese Literature, Keene claims Murasaki wrote the "supreme work of Japanese fiction" by drawing on traditions of waka court diaries, and earlier monogatari—written in a mixture of Chinese script and Japanese script—such as The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter or The Tales of Ise.[66] She drew on and blended styles from Chinese histories, narrative poetry and contemporary Japanese prose.[63] Adolphson writes that the juxtaposition of formal Chinese style with mundane subjects resulted in a sense of parody or satire, giving her a distinctive voice.[67] Genji follows the traditional format of monogatari—telling a tale—particularly evident in its use of a narrator, but Keene claims Murasaki developed the genre far beyond its bounds, and by doing so created a form that is utterly modern. The story of the "shining prince" Genji is set in the late 9th to early 10th centuries, and Murasaki eliminated from it the elements of fairy tales and fantasy frequently found in earlier monogatari.[68]

The themes in Genji are common to the period, and are defined by Shively as encapsulating "the tyranny of time and the inescapable sorrow of romantic love".[69] The main theme is that of the fragility of life, "the sorrow of human existence", mono no aware—she used the term over a thousand times in Genji.[70] Keene speculates that in her tale of the "shining prince", Murasaki may have created for herself an idealistic escape from court life, which she found less than savory. In Prince Genji she formed a gifted, comely, refined, yet human and sympathetic protagonist. Keene writes that Genji gives a view into the Heian period; for example love affairs flourished, although women typically remained unseen behind screens, curtains or fusuma.[68]

Helen McCullough describes Murasaki's writing as of universal appeal and believes The Tale of Genji "transcends both its genre and age. Its basic subject matter and setting—love at the Heian court—are those of the romance, and its cultural assumptions are those of the mid-Heian period, but Murasaki Shikibu's unique genius has made the work for many a powerful statement of human relationships, the impossibility of permanent happiness in love ... and the vital importance, in a world of sorrows, of sensitivity to the feelings of others."[71] Prince Genji recognizes in each of his lovers the inner beauty of the woman and the fragility of life, which according to Keene, makes him heroic. The story was popular: Emperor Ichijō had it read to him, even though it was written in Japanese. By 1021 all the chapters were known to be complete and the work was sought after in the provinces where it was scarce.[68][72]

Legacy[edit]

Murasaki's reputation and influence have not diminished since her lifetime when she, with other Heian women writers, was instrumental in developing Japanese into a written language.[73] Her writing was required reading for court poets as early as the 12th century as her work began to be studied by scholars who generated authoritative versions and criticism. Within a century of her death she was highly regarded as a classical writer.[72] In the 17th century, Murasaki's work became emblematic of Confucian philosophy and women were encouraged to read her books. In 1673 Kumazawa Banzan argued that her writing was valuable for its sensitivity and depiction of emotions. He wrote in his Discursive Commentary on Genji that when "human feelings are not understood the harmony of the Five Human Relationships is lost."[74]

The Tale of Genji was copied and illustrated in various forms as early as a century after Murasaki's death. The Genji Monogatari Emaki, is a late Heian era 12th-century handscroll, consisting of four scrolls, 19 paintings, and 20 sheets of calligraphy. The illustrations, definitively dated to between 1110 and 1120, have been tentatively attributed to Fujiwara no Takachika and the calligraphy to various well-known contemporary calligraphers. The scroll is housed at the Gotoh Museum and the Tokugawa Art Museum.[75]

Female virtue was tied to literary knowledge in the 17th century, leading to a demand for Murasaki or Genji inspired artifacts, known as genji-e. Dowry sets decorated with scenes from Genji or illustrations of Murasaki became particularly popular for noblewomen: in the 17th century genji-e symbolically imbued a bride with an increased level of cultural status; by the 18th century they had come to symbolize marital success. In 1628, Tokugawa Iemitsu's daughter had a set of lacquer boxes made for her wedding; Prince Toshitada received a pair of silk genji-e screens, painted by Kanō Tan'yū as a wedding gift in 1649.[76]

Murasaki became a popular subject of paintings and illustrations highlighting her as a virtuous woman and poet. She is often shown at her desk in Ishimyama Temple, staring at the moon for inspiration. Tosa Mitsuoki made her the subject of hanging scrolls in the 17th century.[77] The Tale of Genji became a favorite subject of Japanese ukiyo-e artists for centuries with artists such as Hiroshige, Kiyonaga, and Utamaro illustrating various editions of the novel.[78] While early Genji art was considered symbolic of court culture, by the middle of the Edo period the mass-produced ukiyo-e prints made the illustrations accessible for the samurai classes and commoners.[79]

In Envisioning the "Tale of Genji" Shirane observes that "The Tale of Genji has become many things to many different audiences through many different media over a thousand years ... unmatched by any other Japanese text or artifact."[79] The work and its author were popularized through its illustrations in various media: emaki (illustrated handscrolls); byōbu-e (screen paintings), ukiyo-e (woodblock prints); films, comics, and in the modern period, manga.[79] In her fictionalized account of Murasaki's life, The Tale of Murasaki: A Novel, Liza Dalby has Murasaki involved in a romance during her travels with her father to Echizen Province.[24]

The Tale of the Genji is recognized as an enduring classic. McCullough writes that Murasaki "is both the quintessential representative of a unique society and a writer who speaks to universal human concerns with a timeless voice. Japan has not seen another such genius."[65] Keene writes that The Tale of Genji continues to captivate, because, in the story, her characters and their concerns are universal. In the 1920s, when Waley's translation was published, reviewers compared Genji to Austen, Proust, and Shakespeare.[80] Mulhern says of Murasaki that she is similar to Shakespeare, who represented his Elizabethan England, in that she captured the essence of the Heian court and as a novelist "succeeded perhaps even beyond her own expectations."[81] Like Shakespeare, her work has been the subject of reams of criticism and many books.[81]

Kyoto held a year-long celebration commemorating the 1000th anniversary of Genji in 2008, with poetry competitions, visits to the Tale of Genji Museum in Uji and Ishiyama-dera (where a life size rendition of Murasaki at her desk was displayed), and women dressing in traditional 12-layered Heian court Jūnihitoe and ankle-length hair wigs. The author and her work inspired museum exhibits and Genji manga spin-offs.[15] The design on the reverse of the first 2000 yen note commemorated her and The Tale of Genji.[82] A plant bearing purple berries has been named after her.[83]

A Genji Album, only in the 1970s dated to 1510, is housed at Harvard University. The album is considered the earliest of its kind and consists of 54 paintings by Tosa Mitsunobu and 54 sheets of calligraphy on shikishi paper in five colors, written by master calligraphers. The leaves are housed in a case dated to the Edo period, with a silk frontispiece painted by Tosa Mitsuoki, dated to around 1690. The album contains Mitsuoki's authentication slips for his ancestor's 16th-century paintings.[84]

Gallery[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Bowring believes her date of birth most likely to have been 973; Mulhern places it somewhere between 970 and 978, and Waley claims it was 978. See Bowring (2004), 4; Mulhern (1994), 257; Waley (1960), vii.

- ^ a b c d Shirane (2008b), 293

- ^ a b c d Henshall (1999), 24–25

- ^ Shirane (1987), 215

- ^ a b c d e f g Bowring (2004), 4

- ^ Chokusen Sakusha Burui 勅撰作者部類

- ^ a b c d Mulhern (1994), 257–258

- ^ a b c d Inge (1990), 9

- ^ a b Mulhern (1991), 79

- ^ Adolphson (2007), 111

- ^ Seven women were named in the entry, with the actual names of four women known. Of the remaining three women, one was not a Fujiwara, one held a high rank and therefore had to be older, leaving the possibility that the third, Fujiwara no Takako, was Murasaki. See Tsunoda (1963), 1–27

- ^ Ueno (2009), 254

- ^ a b c d e f g h Shirane (1987), 218

- ^ a b Puette (1983), 50–51

- ^ a b Green, Michelle. "Kyoto Celebrates a 1000-Year Love Affair". (December 31, 2008). The New York Times. Retrieved August 9, 2011

- ^ Bowring (1996), xii

- ^ a b Reischauer (1999), 29–29

- ^ qtd in Bowring (2004), 11–12

- ^ a b Perez (1998), 21

- ^ qtd in Inge (1990), 9

- ^ a b Knapp, Bettina. "Lady Murasaki's The Tale of the Genji". Symposium. (1992). (46).

- ^ a b c Mulhern (1991), 83–85

- ^ qtd in Mulhern (1991), 84

- ^ a b Tyler, Royall. "Murasaki Shikibu: Brief Life of a Legendary Novelist: c. 973 – c. 1014". (May 2002) Harvard Magazine. Retrieved August 21, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mulhern (1994), 258–259

- ^ Bowring (2004), 4; Mulhern (1994), 259

- ^ a b c Lockard (2008), 292

- ^ a b Shively and McCullough (1999), 67–69

- ^ McCullough (1990), 201

- ^ Bowring (1996), xiv

- ^ a b Bowring (1996), xv–xvii

- ^ According to Mulhern Shōshi was 19 when Murasaki arrived; Waley states she was 16. See Mulhern (1994), 259 and Waley (1960), vii

- ^ Waley (1960), vii

- ^ a b Mulhern (1994), 156

- ^ Waley (1960), xii

- ^ a b Keene (1999), 414–415

- ^ a b Mostow (2001), 130

- ^ qtd in Keene (1999), 414

- ^ Adolphson (2007), 110, 119

- ^ Adolphson (2007), 110

- ^ Bowring (2004), 11

- ^ qtd in Waley (1960), ix–x

- ^ qtd in Mostow (2001), 133

- ^ Mostow (2001), 131, 137

- ^ Waley (1960), xiii

- ^ Waley (1960), xi

- ^ Waley (1960), viii

- ^ Waley (1960), x

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mulhern (1994), 260–261

- ^ a b c d e Shirane (1987), 221–222

- ^ a b Waley (1960), xv

- ^ Bowring (2004), 3

- ^ Waley (1960), xiv

- ^ Aston (1899), 93

- ^ Bowring (2004), 5

- ^ Mulhern (1996), 259

- ^ Mason (1997), 81

- ^ Kodansha International (2004), 475, 120

- ^ Shirane (2008b), 2, 113–114

- ^ Frédéric (2005), 594

- ^ McCullough (1990), 16

- ^ Shirane (2008b), 448

- ^ a b Mulhern (1994), 262

- ^ McCullough (1990), 9

- ^ a b Shively (1999), 445

- ^ Keene (1988), 75–79, 81–84

- ^ Adolphson (2007), 121–122

- ^ a b c Keene (1988), 81–84

- ^ Shively (1990), 444

- ^ Henshall (1999), 27

- ^ McCullough (1999), 9

- ^ a b Bowring (2004), 79

- ^ Bowring (2004), 12

- ^ qtd in Lillehoj (2007), 110

- ^ Frédéric (2005), 238

- ^ Lillehoj (2007), 110–113

- ^ Lillehoj, 108–109

- ^ Geczy (2008), 13

- ^ a b c Shirane (2008a), 1–2

- ^ Keene (1988), 84

- ^ a b Mulhern (1994), 264

- ^ "Japanese Feminist to Adorn Yen". (February 11, 2009). CBSNews.com. Retrieved August 11, 2011.

- ^ Kondansha (1983), 269

- ^ McCormick (2003), 54–56

Sources[edit]

- Adolphson, Mikhael; Kamens, Edward and Matsumoto, Stacie. Heian Japan: Centers and Peripheries. (2007). Honolulu: Hawaii UP. ISBN 978-0-8248-3013-7

- Aston, William. A History of Japanese Literature. (1899). London: Heinemann.

- Bowring, Richard John (ed). "Introduction". in The Diary of Lady Murasaki. (1996). London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-043576-4

- Bowring, Richard John (ed). "Introduction". in The Diary of Lady Murasaki. (2005). London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-043576-4

- Bowring, Richard John (ed). "The Cultural Background". in The Tale of Genji. (2004). Cambridge: Cambridge UP. ISBN 978-0-521-83208-3

- Frédéric, Louis. Japan Encyclopedia. (2005). Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP. ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5

- Geczy, Adam. Art: Histories, Theories and Exceptions. (2008). London: Oxford International Publishers. ISBN 978-1-84520-700-7

- Inge, Thomas. "Lady Murasaki and the Craft of Fiction". (May 1990) Atlantic Review. (55). 7–14.

- Henshall, Kenneth G. A History of Japan. (1999). New York: St. Martin's. ISBN 978-0-312-21986-4

- Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan. (1983) New York: Kōdansha. ISBN 978-0-87011-620-9

- Keene, Donald. Seeds in the Heart: Japanese Literature from Earliest times to the Late Sixteenth Century. (1999). New York: Columbia UP. ISBN 978-0-231-11441-7

- Keene, Donald. The Pleasures of Japanese Literature. (1988). New York: Columbia UP. ISBN 978-0-231-06736-2

- The Japan Book: A Comprehensive Pocket Guide. (2004). New York: Kodansha International. ISBN 978-4-7700-2847-1

- Lillehoj, Elizabeth. Critical Perspectives on Classicism in Japanese Painting, 1600–17. (2004). Honolulu: Hawaii UP. ISBN 978-0-8248-2699-4

- Lockard, Craig. Societies, Networks, and Transitions, Volume I: To 1500: A Global History. (2008). Boston: Wadsworth. ISBN 978-1-4390-8535-6

- Mason, R. H. P. and Caiger, John Godwin. A History of Japan. (1997). North Clarendon VT:Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8048-2097-4

- McCormick, Melissa. "Genji Goes West: The 1510 Genji Album and the Visualization of Court and Capital". (March 2003). Art Bulletin. (85). 54–85

- McCullough, Helen. Classical Japanese Prose: An Anthology. (1990). Stanford CA: Stanford UP. ISBN 978-0-8047-1960-5

- Mostow, Joshua. "Mother Tongue and Father script: The relationship of Sei Shonagon and Murasaki Shikibu". in Copeland, Rebecca L. and Ramirez-Christensen Esperanza (eds). The Father-Daughter Plot: Japanese Literary Women and the Law of the Father. (2001). Honolulu: Hawaii UP. ISBN 978-0-8248-2438-9

- Mulhern, Chieko Irie. Heroic with Grace: Legendary Women of Japan. (1991). Armonk NY: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-87332-527-1

- Mulhern, Chieko Irie. Japanese Women Writers: a Bio-critical Sourcebook. (1994). Westport CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-25486-4

- Perez, Louis G. The History of Japan. (1990). Westport CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-30296-1

- Puette, William J. The Tale of Genji: A Reader's Guide. (1983). North Clarendon VT: Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8048-3331-8

- Reschauer, Edwin. Japan: The Story of a Nation. (1999). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-557074-5

- Shirane, Haruo. The Bridge of Dreams: A Poetics of "The Tale of Genji". (1987). Stanford CA: Stanford UP. ISBN 978-0-8047-1719-9

- Shirane, Haruo. Envisioning the Tale of Genji: Media, Gender, and Cultural Production. (2008a). New York: Columbia UP. ISBN 978-0-231-14237-3

- Shirane, Haruo. Traditional Japanese Literature: An Anthology, Beginnings to 1600. (2008b). New York: Columbia UP. ISBN 978-0-231-13697-6

- Shively, Donald and McCullough, William H. The Cambridge History of Japan: Heian Japan. (1999). Cambridge UP. ISBN 978-0-521-22353-9

- Tsunoda, Bunei. "Real name of Murasahiki Shikibu". Kodai Bunka (Cultura antiqua). (1963) (55). 1–27.

- Ueno, Chizuko. The Modern Family in Japan: Its Rise and Fall. (2009). Melbourne: Transpacific Press. ISBN 978-1-876843-56-4

- Waley, Arthur. "Introduction". in Shikibu, Murasaki, The Tale of Genji: A Novel in Six Parts. translated by Arthur Waley. (1960). New York: Modern Library.

External links[edit]

| Library resources about Murasaki Shikibu |

| By Murasaki Shikibu |

|---|

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Murasaki Shikibu |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Murasaki Shikibu. |

- Rozan-ji Temple, Kyoto

- Works by Murasaki Shikibu at Open Library

- Works by Murasaki Shikibu at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

Original Text

The Tale of Genji was written by a Japanese noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu in the early eleventh century. Both the original and the modern Japanese versions are available online. The website at the University of Virginia kindly provided an option to read the work in three parallel frames: original, modern Japanese, and romaji versions.

Incomplete Translations

Suematsu, Kenchō. Genji Monogatari : The Most Celebrated of the Classical Japanese Romances. London: Trubner, 1882.

- First translation into English

- Considered poor quality

- Only few chapters were completed

Helen McCullough. Genji & Heike: Selections from The Tale of Genji and The Tale of the Heike. Stanford: Stanford University Press., 1994.

- Only selected chapters

- Only the first half of the book

Complete English Translations

Arthur Waley. The Tale of Genji. London: George Allen & Unwin. (1926-1933)

- Very free translation

- Omitted several chapters

- Great achievement of its time

- Very well received at the time of publication

Edward Seidensticker. The Tale of Genji. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. (1976)

- Closer to original than Waley

- Some liberties were taken to improve readability

- Characters are identified by name instead of title as in the original

- Succinct yet naturally flowing narration

- Early editions of the book have many typos

Royall Tyler. The Tale of Genji. New York: Viking Press. (2001)

- Closest to the original than any previous translation

- Extensive notes and commentaries about poetical and cultural aspects

- Attempted to mimic the original style of Murasaki

- Used titles, just like the original, instead of names

- Text may be difficult to follow because titles change over time

- Poems are somewhat wordy

First Sentence

Arthur Waley: ”At the Court of an Emperor (he lived it matters not when) there was among the many gentlewomen of the Wardrobe and Chamber one, who though she was not of very high rank was favored far beyond all the rest.”

Edward Seidensticker: ”In a certain reign there was a lady not of the first rank whom the emperor loved more than any of the others.”

Royall Tyler: ”In a certain reign (whose can it have been?) someone of no very great rank, among all His Majesty’s Consorts and Intimates, enjoyed exceptional favor.”

Chapter Five: “Murasaki”

Genji visits a Buddhist monastery in the mountains

Arthur Waley: “Genji felt very disconsolate. It had begun to rain; a cold wind blew across the hill, carrying with it the sound of a waterfall–audible till then as a gentle intermittent plashing, but now a mighty roar; and with it, somnolently rising and falling, mingled the monotonous chanting of the scriptures. Even the most unimpressionable nature would have been plunged into melancholy by such surroundings. How much the more so Prince Genji, as he lay sleepless on his bed, continually planning and counter-planning.”

Edward Seidensticker: “Genji was not feeling well. A shower passed on a chilly mountain wind, and the sound of the waterfall was higher. Intermittently came a rather sleepy voice, solemn and somehow ominous, reading a sacred text. The most insensitive of men would have been aroused by the scene. Genji was unable to sleep.”

Royall Tyler: “Genji felt quite unwell, and besides, it was now raining a little, a cold mountain wind had set in to blow, and the pool beneath the waterfall had risen until the roar was louder than before. The eerie swelling and dying of somnolent voices chanting the scriptures could hardly fail in such a setting to move the most casual visitor. No wonder Genji, who had so much to ponder, could not sleep. ”

Source: Amazon Customer Review

Poetry

Waley ran the poems right into the text, and Seidensticker set them off as couplets; neither strategy was entirely faithful to the original, though Seidensticker’s was perhaps more effective. Tyler’s solution is to present each as a single sentence broken into two lines, and he makes his task even more difficult by preserving the 5-7-5-7-7 syllabic pattern of waka.

Edward Seidensticker:

Beneath a tree, a locust’s empty shell.

Sadly I muse upon the shell of a lady.

Royall Tyler:

Underneath this tree, where the molting cicada shed her empty shell,

my longing still goes to her, for all I knew her to be.

Choose Your Guide

My favorite translation is by Edward Seidensticker due to its succinct approach, beautiful poems, and natural flow. However, I’ll be reading Royall Tyler’s version because it is close to the original and offers extensive notes about the history.

Janice P. Nimura summarized it very well: “Waley is the most entertaining, Seidensticker the most unobtrusive, and Tyler the most instructive.”

Sue mentioned that there is a new version by Dennis Washburn, a Jane and Raphael Bernstein Professor in Asian Studies at Dartmouth College. He holds a Ph.D. from Yale University in Japanese language and literature.

Some reviews:

“This new version by Dennis Washburn, a professor at Dartmouth, falls somewhere between Seidensticker’s reader-friendly translation and Tyler’s more stringently literal one, resulting in a fluid, elegant rendition.” (Washington Post)

紫式部(むらさきしきぶ、生没年不詳)は、平安時代中期の女性作家、歌人。『源氏物語』の作者と考えられている。中古三十六歌仙、女房三十六歌仙の一人。『小倉百人一首』にも「めぐりあひて 見しやそれとも わかぬまに 雲がくれにし 夜半の月かな」で入選。

屈指の学者、詩人である藤原為時の娘。藤原宣孝に嫁ぎ、一女(大弐三位)を産んだ。夫の死後、召し出されて一条天皇の中宮・藤原彰子に仕えている間に、『源氏物語』を記した[1]。

目次

[非表示]略伝[編集]

藤原北家の出で、越後守・藤原為時の娘で母は摂津守・藤原為信女であるが、幼少期に母を亡くしたとされる。同母の兄弟に藤原惟規がいる(同人の生年も不明であり、式部とどちらが年長かについては両説が存在する[2])ほか、姉がいたことも分かっている。三条右大臣・藤原定方、堤中納言・藤原兼輔はともに父方の曽祖父で一族には文辞を以って聞こえた人が多い。

幼少の頃より当時の女性に求められる以上の才能で漢文を読みこなしたなど、才女としての逸話が多い。54帖にわたる大作『源氏物語』、宮仕え中の日記『紫式部日記』を著したというのが通説、家集『紫式部集』が伝わっている。

父・為時は30代に東宮の読書役を始めとして東宮が花山天皇になると蔵人、式部大丞と出世したが花山天皇が出家すると失職した。10年後、一条天皇に詩を奉じた結果、越前国の受領となる。紫式部は娘時代の約2年を父の任国で過ごす。

長徳4年(998年)頃、親子ほども年の差がある山城守・藤原宣孝と結婚し長保元年(999年)に一女・藤原賢子(大弐三位)を儲けたが、この結婚生活は長く続かずまもなく長保3年4月15日(1001年5月10日)宣孝と死別した。

寛弘2年12月29日(1006年1月31日)、もしくは寛弘3年の同日(1007年1月20日)より、一条天皇の中宮・彰子(藤原道長の長女、のち院号宣下して上東門院)に女房兼家庭教師役として仕え、少なくとも寛弘8年(1012年)頃まで奉仕し続けたようである。

なおこれに先立ち、永延元年(987年)の藤原道長と源倫子の結婚の際に、倫子付きの女房として出仕した可能性が指摘されている。源氏物語の解説書である「河海抄」や「紫明抄」、歴史書の「今鏡」には紫式部の経歴として倫子付き女房であったことが記されている。それらは伝承の類であり信憑性には乏しいが、他にも紫式部日記からうかがえる、新参の女房に対するものとは思えぬ道長や倫子からの格別な信頼・配慮があること、永延元年当時為時は失職しており家庭基盤が不安定であったこと、倫子と紫式部はいずれも曽祖父に藤原定方を持ち遠縁に当たることなどが挙げられる。また女房名からも、為時が式部丞だった時期は彰子への出仕の20年も前であり、さらにその間に越前国の国司に任じられているため、寛弘2年に初出仕したのであれば父の任国「越前」や亡夫の任国・役職の「山城」「右衛門権佐」にちなんだ名を名乗るのが自然で、地位としてもそれらより劣る「式部」を女房名に用いるのは考えがたく、そのことからも初出仕の時期は寛弘2年以前であるという説である[3]。

『詞花集』に収められた伊勢大輔の「いにしへの奈良の都の八重桜 けふ九重ににほひぬるかな」という和歌は宮廷に献上された八重桜を受け取り中宮に奉る際に詠んだものだが、『伊勢大輔集』によればこの役目は当初紫式部の役目だったものを式部が新参の大輔に譲ったものだった。

藤原実資の日記『小右記』長和2年5月25日(1014年6月25日)条で「実資の甥で養子である藤原資平が実資の代理で皇太后彰子のもとを訪れた際『越後守為時女』なる女房が取り次ぎ役を務めた」との記述が紫式部で残された最後のものとし、よって三条天皇の長和年間(1012-1016年)に没したとするのが昭和40年代までの通説だったが、現在では、『小右記』寛仁3年正月5日(1019年2月18日)条で 、実資に応対した「女房」を紫式部本人と認め([4])、さらに、西本願寺本『平兼盛集』巻末逸文に「おなじ宮の藤式部、…式部の君亡くなり…」とある詞書と和歌を、岡一男説[5]の『頼宗集』の逸文ではなく、『定頼集』の逸文と推定し、この直後に死亡したとする萩谷朴説[6]、今井源衛説が存在する。

現在、日本銀行D銀行券 2000円札の裏には小さな肖像画と『源氏物語絵巻』の一部を使用している。

人物[編集]

本名[編集]

紫式部の本名は不明であるが、『御堂関白記』の寛弘4年1月29日(1007年2月19日)の条において掌侍になったとされる記事のある「藤原香子」(かおりこ / たかこ / こうし)とする角田文衛の説もある[7]。この説は発表当時「日本史最大の謎」として新聞報道されるなど、センセーショナルな話題を呼んだ。 但し、この説は仮定を重ねている部分も多く推論の過程に誤りが含まれているといった批判もあり[8]、その他にも、もし紫式部が「掌侍」という律令制に基づく公的な地位を有していたのなら勅撰集や系譜類に何らかの言及があると思えるのにそのような痕跡が全く見えないのはおかしいとする批判も根強くある[9]。その後、萩谷朴の香子説追認論文[10]も提出されたが、未だにこの説に関しての根本的否定は提出されておらず、しかしながら広く認められた説ともなっていないのが現状である。また、香子を「よしこ」とする説もある。

その他の名前[編集]

女房名は「藤式部」。「式部」は父為時の官位(式部省の官僚・式部大丞だったこと)に由来するとする説と同母の兄弟惟規の官位によるとする説とがある[11] 。

現在一般的に使われている「紫式部」という呼称について、「紫」のような色名を冠した呼称はこの時代他に例が無くこのような名前で呼ばれるようになった理由についてはさまざまに推測されているが、一般的には「紫」の称は『源氏物語』または特にその作中人物「紫の上」に由来すると考えられている[12]。

また、上原作和は、『紫式部集』の宣孝と思しき人物の詠歌に「ももといふ名のあるものを時の間に散る桜にも思ひおとさじ」とあることから、幼名・通称を「もも」とする説を提示した[13]。今後の検証が待たれる。

婚姻関係[編集]

紫式部の夫としては藤原宣孝がよく知られており、これまで式部の結婚はこの一度だけであると考えられてきた。しかし、「紫式部=藤原香子」説との関係で、『権記』の長徳3年(997年)8月17日条に現れる「後家香子」なる女性が藤原香子=紫式部であり、紫式部の結婚は藤原宣孝との一回限りではなく、それ以前に紀時文との婚姻関係が存在したのではないかとする説が唱えられている[14]。

『尊卑分脈』において紫式部が藤原道長妾であるとの記述がある(後述)ことは古くからよく知られていたが、この記述については後世になって初めて現れたものであり、事実に基づくとは考えがたいとするのが一般的な受け取り方であった。しかしこれは『紫式部日記』にある「紫式部が藤原道長からの誘いをうまくはぐらかした」といった記述が存在することを根拠として「紫式部は二夫にまみえない貞婦である」とした『尊卑分脈』よりずっと後になって成立した観念的な主張に影響された判断であり、一度式部が道長からの誘いを断った記述が存在し、たとえそのこと自体が事実だとしても、最後まで誘いを断り続けたのかどうかは日記の記述からは不明であり、また当時の婚姻制度や家族制度から見て式部が道長の妾になったとしても法的にも道徳的にも問題があるわけではないのだから、尊卑分脈の記述を否定するにはもっときちんとしたそれなりの根拠が必要であり、この尊卑分脈の記述はもっと真剣に検討されるべきであるとする主張もある[要出典]。

日本紀の御局[編集]

『源氏の物語』を女房に読ませて聞いた一条天皇が作者を褒めてきっと日本紀(『日本書紀』のこと)をよく読みこんでいる人に違いないと言ったことから「日本紀の御局」とあだ名されたとの逸話があるが、これには女性が漢文を読むことへの揶揄があり本人には苦痛だったようであるとする説が通説である。

| “ | 「内裏の上の源氏の物語人に読ませたまひつつ聞こしめしけるに この人は日本紀をこそよみたまへけれまことに才あるべし とのたまはせけるをふと推しはかりに いみじうなむさえかある と殿上人などに言ひ散らして日本紀の御局ぞつけたりけるいとをかしくぞはべるものなりけり」(『紫式部日記』) | ” |

生没年[編集]

当時の受領階級の女性一般がそうであるように、紫式部の生没年を明確な形で伝えた記録は存在しない。そのため紫式部の生没年についてはさまざまな状況を元に推測したさまざまな説が存在しており定説が無い状態である。

生年については両親が婚姻関係になったのが父の為時が初めて国司となって播磨の国へ赴く直前と考えられることからそれ以降であり、かつ同母の姉がいることからそこからある程度経過した時期であろうとはみられるものの、同母の兄弟である藤原惟規とどちらが年長であるのかも不明であり、以下のようなさまざまな説が混在する[15]。

- 970年(天禄元年)説(今井源衛[16]・稲賀敬二[17]・後藤祥子説)

- 972年(天禄3年)説(小谷野純一説[18])

- 973年(天延元年)説(岡一男説[19])

- 974年(天延2年)説(萩谷朴説[20])

- 975年(天延3年)説(南波浩説[21])

- 978年(天元元年)説(安藤為章(紫家七論)・与謝野晶子・島津久基[22]説)資料・作品等から1008年(寛弘5年)に30歳位と推測されることなどを理由とする。

また没年についても、紫式部と思われる「為時女なる女房」の記述が何度か現れる藤原実資の日記『小右記』において、長和2年5月25日(1014年6月25日)の条で「実資の甥で養子である藤原資平が実資の代理で皇太后彰子のもとを訪れた際『越後守為時女』なる女房が取り次ぎ役を務めた」との記述が紫式部について残された明確な記録のうち最後のものであるとする認識が有力なものであったが、これについても異論が存在し、これ以後の明確な記録が無いこともあって、以下のようなさまざまな説が存在している[23]。

- 1014年(長和3年)2月の没とする説(岡一男説[24])。なお、岡説は前掲の西本願寺本『平兼盛集』の逸文に「おなじみやのとうしきぶ、おやのゐなかなりけるに、『いかに』などかきたりけるふみを、しきぶのきみなくなりて、そのむすめ見はべりて、ものおもひはべりけるころ、見てかきつけはべりける」とある詞書を、賢子と交際のあった藤原頼宗の『頼宗集』の残欠が混入したものと仮定している。

- 1016年(長和5年)頃没とする与謝野晶子の説[25](『小右記』長和5年4月29日(1016年6月6日)条にある父・為時の出家を近しい身内(式部)の死と結びつける説が有力であることによる)

- 1017年(寛仁元年)以降とする山中裕による説(光源氏が「太上天皇になずらふ」存在となったのは紫式部が同年の敦明親王の皇太子辞退と准太上天皇の待遇授与の事実を知っていたからであるとして同年以後の没とする)[26]。

- 1019年(寛仁3年)『小右記』正月5日条に実資と相対した「女房」を紫式部と認め、かつ西本願寺本『平兼盛集』巻末逸文を、娘・賢子の交友関係から『定頼集』の逸文と推定して、寛仁3年内の没とする(萩谷朴説[27]) 、(今井源衛説)。

- 1025年(万寿2年)以後の没とする安藤為章による説(「楚王の夢」『栄花物語』の解釈を根拠として娘の大弐三位が後の後冷泉天皇の乳母となった時点で式部も生存していたと考えられるとする。)

- 1031年(長元4年)没とする角田文衛による説(『続後撰集』に長元3年8月(1030年)の作品が確認出来ることなどを理由とする。[28])

墓所[編集]

紫式部の墓と伝えられるものが京都市北区紫野西御所田町(堀川北大路下ル西側)に残されている。紫式部の墓とされるものは小野篁の墓とされるものに隣接して建てられている。この場所は淳和天皇の離宮があり、紫式部が晩年に住んだと言われ後に大徳寺の別坊となった雲林院百毫院の南にあたる。この地に紫式部の墓が存在するという伝承は、古くは14世紀中頃の源氏物語の注釈書『河海抄』(四辻善成)に、「式部墓所在雲林院白毫院南 小野篁墓の西なり」と明記されており、15世紀後半の注釈書『花鳥余情』(一条兼良)、江戸時代の書物『扶桑京華志』や『山城名跡巡行志』、『山州名跡志』にも記されている。1989年に社団法人紫式部顕彰会によって整備されており[29]、京都の観光名所の一つになっている。

その他[編集]

貴族では珍しくイワシが好物であったという説話があるが、元は『猿源氏草紙』で和泉式部の話であり、後世の作話と思われる。

紫式部日記[編集]

人物評[編集]

同時期の有名だった女房たちの人物評が見られる。中でも最も有名なのが『枕草子』作者の清少納言に対する、(以下、意訳)

- 「得意げに真名(漢字)を書き散らしているが、よく見ると間違いも多いし大した事はない」(「清少納言こそ したり顔にいみじうはべりける人 さばかりさかしだち 真名書き散らしてはべるほども よく見れば まだいと足らぬこと多かり」『紫日記』黒川本)、

- 「こんな人の行く末にいいことがあるだろうか(いや、ない)」(「そのあだになりぬる人の果て いかでかはよくはべらむ」『紫日記』黒川本)

などの殆ど陰口ともいえる辛辣な批評である。これらの表記は近年に至るまで様々な憶測や、ある種野次馬的な興味(紫式部が清少納言の才能に嫉妬していたのだ、など)を持って語られている。もっとも本人同士は年齢や宮仕えの年代も10年近く異なるため、実際に面識は無かったものと見られている。近年では、『紫式部日記』の政治的性格を重視する視点から、清少納言の『枕草子』が故皇后・定子を追懐し、紫式部の主人である中宮・彰子の存在感を阻んでいることに苛立ったためとする解釈が提出されている。[30]同輩であった女流歌人の和泉式部(「素行は良くないが、歌は素晴らしい」など)や赤染衛門(「家柄は良くないが、歌は素晴らしい」など)には、否定的な批評もありながらも概ね好感を見せている。

道長妾[編集]

紫式部日記及び同日記に一部記述が共通の『栄花物語』には、夜半に道長が彼女の局をたずねて来る一節があり鎌倉時代の公家系譜の集大成である『尊卑分脈』(『新編纂図本朝尊卑分脉系譜雑類要集』)になると、「上東門院女房 歌人 紫式部是也 源氏物語作者 或本雅正女云々 為時妹也云々 御堂関白道長妾」と紫式部の項にはっきり道長妾との註記が付くようになるが、彼女と道長の関係は不明である。

主な作品[編集]

紫式部を題材とした作品[編集]

- 杉本苑子『散華 紫式部の生涯』

- (中央公論新社、平成3年(1991年)) 上 ISBN 4-12-001994-2、下 ISBN 4-12-001995-0

- (中公文庫、平成6年(1994年)) 上 ISBN 4-12-202060-3、下 ISBN 4-12-202075-1

- 三枝和子『小説 紫式部香子の恋』

- (読売新聞社、平成3年(1991年)) ISBN 4-643-91087-9

- (福武文庫、平成6年(1994年)) ISBN 4-8288-5702-8

- さかぐち直美『紫式部―はなやかな源氏絵巻 (学研まんが人物日本史 平安時代)』

- (学研、昭和56年(1981年))

- あおむら純『紫式部(小学館版学習まんが 少年少女人物日本の歴史)』

- (小学館、昭和59年(1984年))

紫式部学会[編集]

紫式部学会とは昭和7年(1932年)6月4日に東京帝国大学文学部国文学科主任教授であった藤村作(会長)、東京帝国大学文学部国文学科教授であった久松潜一(副会長)、東京帝国大学文学部国文学研究室副手であった池田亀鑑(理事長)らによって源氏物語に代表される古典文学の啓蒙を目的として設立された学会である。昭和39年(1964年)1月より事務局が神奈川県横浜市鶴見区にある鶴見大学文学部日本文学科研究室に置かれている。現在の会長は秋山虔がつとめている。

講演会を実施したり源氏物語を題材にした演劇の上演を後援したりしているほか以下の出版物を刊行している。

- 機関誌『むらさき』戦前(昭和9年(1934年)8月~昭和19年(1944年)6月)は月刊、戦後版(昭和37年(1962年)~)は年刊

- 論文集『研究と資料 古代文学論叢』昭和44年(1969年)6月~年刊 武蔵野書院より刊行

参考文献[編集]

- 岡一男『増訂 源氏物語の基礎的研究 -紫式部の生涯と作品-』東京堂出版、1966年8月。

- 堀内秀晃「紫式部諸説一覧」阿部秋生編『諸説一覧源氏物語』明治書院、1970年8月、pp.. 335-354。

- 萩谷朴「解説・作者について」『紫式部日記全注釈』下巻、角川書店、1973年8月、pp.. 467-508 ISBN ISBN 978-4047610217

- 今井源衛『今井源衛著作集 3 紫式部の生涯』笠間書院、2003年7月30日 ISBN 4-305-60082-X

- 角田文衞『紫式部伝 その生涯と源氏物語』法藏館、2007年1月25日 ISBN 978-4-8318-7664-5

- 倉本一宏『紫式部と平安の都』吉川弘文館、2014年9月18日 ISBN 978-4642067867

脚注[編集]

- ^ 『百科事典マイペディア』、「紫式部」の項、平凡社、2006年。

- ^ 堀内秀晃「紫式部諸説一覧 二 惟規との前後関係」阿部秋生編『諸説一覧源氏物語』明治書院、1970年8月、pp. 338。

- ^ 徳満澄雄「紫式部は鷹司殿倫子の女房であったか」『語文研究』第62号、九州大学国語国文学会、1986年、pp.. 1-12。

- ^ 角田文衞「紫式部の本名」『紫式部とその時代』(角川書店、1966年)。

- ^ 岡一男「紫式部の晩年の生活附説 紫式部の没年について 『平兼盛集』を新資料として」『増訂 源氏物語の基礎的研究 紫式部の生涯と作品』東京堂出版、1966年、pp.. 143-170。

- ^ 萩谷朴「解説・作者について」『紫式部日記全注釈』下巻、角川書店、1973年8月、pp.. 467-508 ISBN ISBN 978-4047610217

- ^ 角田文衞「紫式部の本名」『紫式部とその時代』(角川書店、1966年)収録。なお、発表後にあった批判に対する反論と誤謬の訂正を加え、「紫式部伝 その生涯と源氏物語」に角田説は集大成されている。

- ^ 今井源衛「紫式部本名香子説を疑う」『国語国文』1965年1月号 のち『王朝文学の研究』(角川書店、1976年および『今井源衛著作集 3 紫式部の生涯』に収録

- ^ 岡一男「紫式部の本名 藤原香子説の根本的否定」『増訂 源氏物語の基礎的研究 -紫式部の生涯と作品-』東京堂出版、1966年8月、pp.. 598-613。

- ^ 萩谷朴「解説・作者について」『紫式部日記全注釈』下巻、角川書店、1973年8月、pp.. 467-508 ISBN ISBN 978-4047610217

- ^ 堀内秀晃「紫式部諸説一覧 九 式部と呼ばれた理由」阿部秋生編『諸説一覧源氏物語』明治書院、1970年8月、pp. 348。

- ^ 堀内秀晃「紫式部諸説一覧 10 藤式部が紫式部と呼ばれた理由」阿部秋生編『諸説一覧源氏物語』明治書院、1970年8月、pp,. 348-350。

- ^ 上原作和「紫式部伝4-生い立ちI-幼名「もも」説の提唱」上原作和・編集『人物で読む源氏物語』「藤壺の宮」巻、勉誠出版、2005年5月、pp.. 317-319 ISBN 978-4-585-01144-6

- ^ 上原作和「ある紫式部伝 本名・藤原香子説再評価のために」南波浩『紫式部の方法 源氏物語 紫式部集 紫式部日記』笠間書院、2002年11月、pp.. 469-492。 ISBN 4-305-70245-2

- ^ 堀内秀晃「紫式部諸説一覧 出生年次」阿部秋生編『諸説一覧源氏物語』明治書院、1970年8月、pp.. 336-338。

- ^ 今井源衛「紫式部の出生年度」『文学研究』第63輯、1966年3月。のち『王朝文学の研究』角川書店、1970年。及び『今井源衛著作集 3 紫式部の生涯』笠間書院、2003年7月30日、pp.. 181-205。 ISBN 4-305-60082-X

- ^ 稲賀敬二「天禄元年ころの誕生か」『日本の作家12 源氏の作者 紫式部』新典社、1982年11月、pp.. 13-14。 ISBN 978-4787970121

- ^ 小谷野純一「解説」『紫式部日記』笠間書院、2007年4月、pp.. 197-227 ISBN 978-4-305-70420-7

- ^ 岡一男「紫式部の生涯」『源氏物語講座 第二巻作者と時代』有精堂、1971年12月、pp.. 1-58

- ^ 萩谷朴「解説・作者について」『紫式部日記全注釈』下巻、角川書店、1973年8月、pp.. 467-508 ISBN ISBN 978-4047610217

- ^ 南波浩『紫式部全評釈』笠間書院、1983年

- ^ 島津久基『日本文学者評伝全書 紫式部』青梧堂、1943年。

- ^ 堀内秀晃「紫式部諸説一覧 紫式部の没年」阿部秋生編『諸説一覧源氏物語』明治書院、1970年8月、pp.. 352-354。

- ^ 岡一男「紫式部の晩年の生活附説 紫式部の没年について 『平兼盛集』を新資料として」『増訂 源氏物語の基礎的研究 紫式部の生涯と作品』東京堂出版、1966年、pp.. 143-170。

- ^ 与謝野晶子「紫式部新考」『太陽』昭和3年2月号。のち『日本文学研究資料叢書 源氏物語 1』 有精堂、1969年10月、pp.. 1-16。 ISBN 4-640-30017-4

- ^ 山中裕「紫式部の生涯と後宮」(書き下ろし)『源氏物語の史的研究』(思文閣出版、1997年6月1日) ISBN 978-4-7842-0941-5

- ^ 萩谷朴「解説・作者について」『紫式部日記全注釈』下巻、角川書店、1973年8月、pp.. 467-508 ISBN ISBN 978-4047610217

- ^ 角田文衞「紫式部の歿年」『紫式部とその時代』(角川書店、1971年)所収、のち「紫式部伝―その生涯と『源氏物語』」pp.. 216-241。

- ^ 社団法人紫式部顕彰会

- ^ 山本淳子「『紫式部日記』清少納言批評の背景」(『古代文化』2001年9月号)

関連項目[編集]

- 石山寺 - 源氏物語執筆の場所とされる

- 紫式部公園 - 娘時代の約2年を過ごした父の任国・越前国府(福井県越前市)に造られた

- 紫式部文学賞 - 京都府宇治市主催の女流作家のための文学賞

- 宇治市源氏物語ミュージアム

- 大雲寺 - 若紫の舞台・紫式部の曾祖父が初代住職

- 廬山寺 - 紫式部邸宅址

- アニーローリー - 日本語の歌詞(題名:才女)で紫式部について歌っている。

外部リンク[編集]